That's a pretty good Searls impression

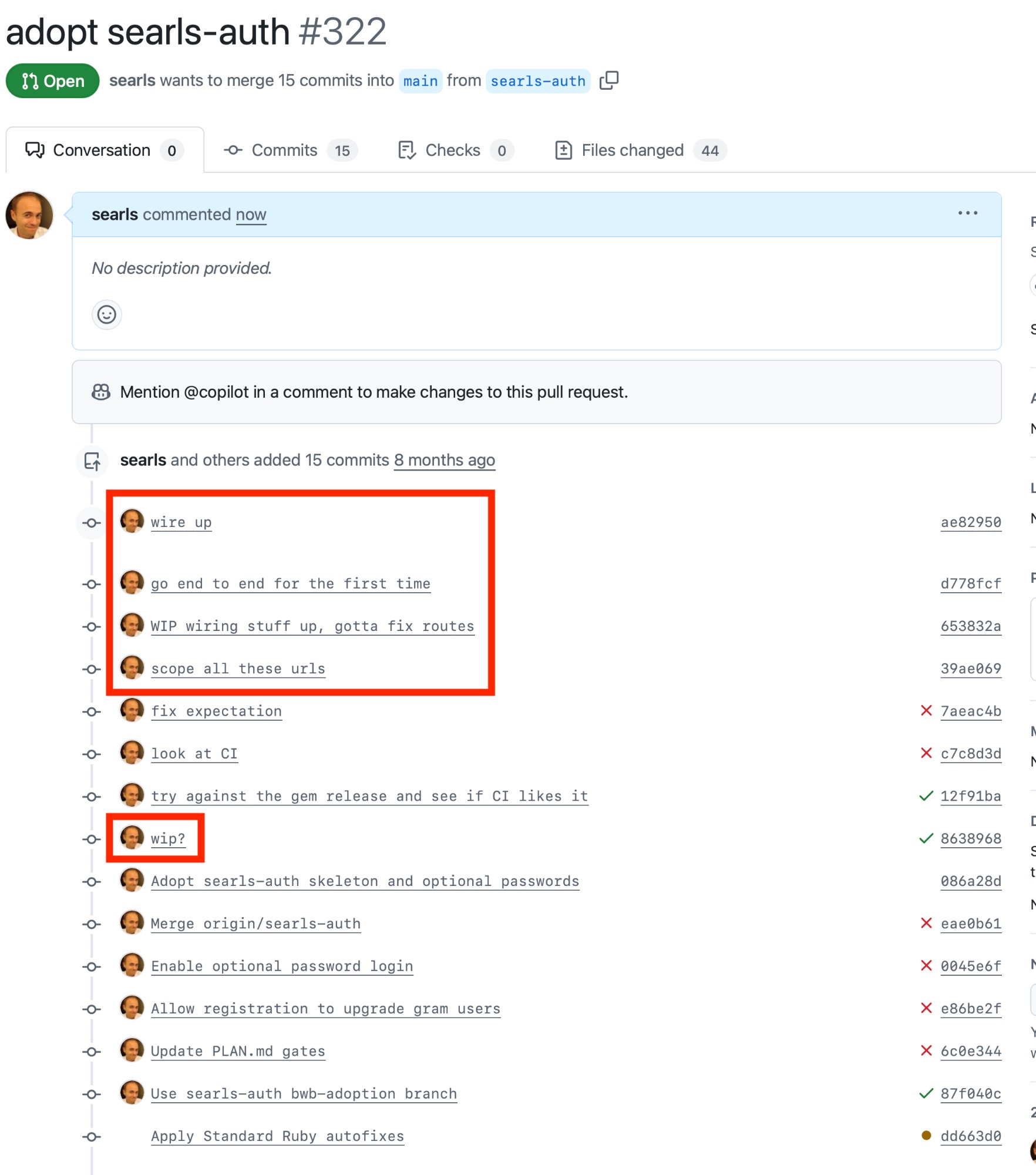

We were gone most of the day so I told Codex CLI to migrate Better with Becky to my searls-auth gem and to commit & push regularly to a PR so I could review remotely. Just noticed that it must have looked through the git history in order to write commit messages that match my own. Seriously thought I wrote half of these before I realized as much.

Uncanny, but appreciated.

If you don't count Halo LAN parties, I probably sank more time into Knights of the Old Republic on the original Xbox than any other game. By taking the classic tabletop mechanics they were known for and theming it with a setting that didn't bore me to tears, Bioware really hooked me. I even played through every campaign quest of the middling The Old Republic MMO, which are hundreds of hours I'll never get back.

Last night, this announcement just dropped, as reported by Jordan Miller at VGC:

Announced at The Game Awards, the game is being directed by Casey Hudson, the director of the original Knights of the Old Republic game.

"Developed by Arcanaut Studios in collaboration with Lucasfilm Games, Star Wars: Fate of the Old Republic is a new single-player narrative-driven action RPG and spiritual successor to Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic," according to a press release.

"Led by Casey Hudson, Game director of the original Star Wars: Knight of the Old Republic and the Mass Effect trilogy, the team of veteran game developers and storytellers at Arcanaut Studios is crafting an epic interactive adventure across a galaxy on the brink of rebirth, where every decision shapes your path towards light or darkness."

And with this teaser:

To learn that the director of both KOTOR and Mass Effect is coming out with a new game in a similar setting is really exciting. Hudson took some well-deserved shit for Mass Effect 3's ending, but he's spent enough time in the wilderness at this point to earn another shot.

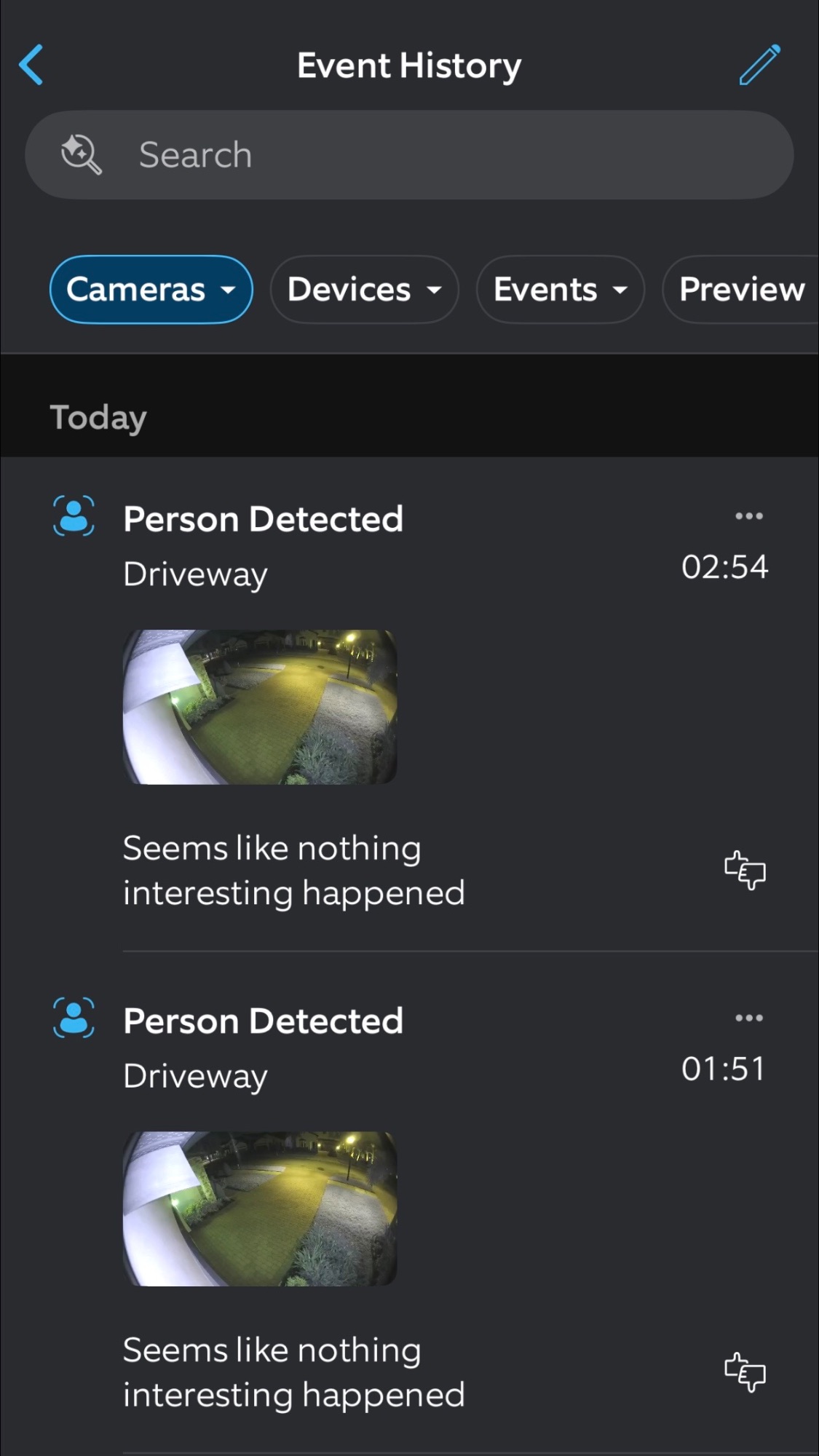

Seems like nothing interesting happened

I turned on Ring's new AI description feature for its cameras a couple weeks ago. Opened my event history for the first time since then and was kind of impressed by the honest assessment of what goes on around here.

I use both Instacart and ChatGPT, and just tried this. It's an absolute joke. Broken. If you can't oneshot a full order, you'll "slip out" of agentic mode and into normal conversation. Total Junk. techcrunch.com/2025/12/08/you-can-buy-your-instacart-groceries-without-leaving-chatgpt/

ChatGPT 5.1 explains why it hallucinates

Because I'm a glutton for punishment, from time to time I'll, "rub an LLM's nose in it," when it fucks up a task. I know the chatbot can't learn from this, and I know I'm just wasting 8¢ of some idiot investor's money, but I do it anyway.

Dion Lim wrote a pretty good angle on what the market correction will actually do:

The first web cycle burned through dot-com exuberance and left behind Google, Amazon, eBay, and PayPal: the hardy survivors of Web 1.0. The next cycle, driven by social and mobile, burned again in 2008–2009, clearing the underbrush for Facebook, Airbnb, Uber, and the offspring of Y Combinator. Both fires followed the same pattern: excessive growth, sudden correction, then renaissance.

Now, with AI, we are once again surrounded by dry brush.

I think in one of our discussions before our Hot Fix episode, Scott Werner and I used the same analogy—that a recessionary fire will be necessary to clear the overgrowth and make room for companies better-adapted to the post-AI world to innovate—and the author seems to have picked up that metaphor and run with it.

I think the important thing to take away here is that most people hear this and their instinct is to hide. "Well, a fire is coming, I should sit on the sidelines and wait things out." Apart from the foolishness of trying to time the market, this is especially bad advice amid a market wildfire. One of the most actually-useful pieces of advice I've offered founders and investors over the years is the importance of investing through into and through the downturn.

My preferred way to do that is, of course, profitably. However, if you're ever going to tolerate operating at break-even margins or (God forbid) a loss, the best time to do that is when everyone else is cashing out, laying people off, or closing up shop. Hunker down through the cleansing and the act of persevering will generally see a company emerge as a far more resilient operation that finds itself in a far less competitive environment.

I learned this during the Web 2.0 during the Great Recession. Pillar Technology started hiring some of the most talented, most engaged developers in central Ohio and southeast Michigan throughout 2009-2011 when other firms were still hobbled by downsizing. And they paid a premium, too (I nearly doubled my salary to work there!). But when they came out the other end of the recession, they were five times the size, sold into half a dozen verticals, had developed a national profile of clients, and the owner was able to cash out to Accenture for a high-eight figure exit.

When other people get scared, get aggressive.

Video of this episode is up on YouTube:

I'm experiencing what breathing out of my nose properly feels like for the first time. Everything is new and wondrous and I've never felt so optimistic. This sensation lasted for two days and now I'm used to it and existence is once again pain.

Share your existential musings at podcast@searls.co and I'll nod and sigh along. I might even nod and sigh performatively for you on the show!

Important ground covered in this episode:

Amazing to think that—adjusting for inflation—the entirety of Warner Brothers is worth significantly less than Activision. Call of Duty and Candy Crush matter more than Harry Potter, HBO, DC comics, etc. reuters.com/legal/transactional/netflix-agrees-buy-warner-bros-discoverys-studios-streaming-division-2025-12-05/

Fit a 5090 gaming rig in a backpack

I spent my holiday weekend gaining massive respect for the small-form factor (SFF) PC gaming community. Holy shit, was this a pain in the ass. BUT, it's a fraction the size, way faster, and whisper quiet compared to my outgoing build. Glad I did it.

😮💨

I'd do it all again

This is a copy of the Searls of Wisdom newsletter delivered to subscribers on November 25, 2025.

Hello! We're all busy, so I'm going to try my hand at writing less this time. Glance over at your scrollbar now to see how I did. Since we last corresponded:

- Dropped in on the Ruby AI podcast

- Added a new cable to the increasing number of cables plugging my face into my computer, which shipped with some pretty glaring issues, some of which I talked about

- Found somebody else saying that, in the short term, AI codegen is going to dramatically increase the demand for software as the supply constraint on programming eases

- Made an open source library called Straight-to-Video that performs client-side remuxing and transcoding of videos, beating them into shape for upload via the Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok APIs

- Hosted my brother after he sold his house, which (of course) coincided with nonstop power and Internet outages. Rather than do something about it, I complained into my microphone

- Mourned the fact iPhone 18 Air apparently got cancelled or delayed to Spring 2027, continuing my losing streak of falling in love with Apple's least popular hardware

- Learned I have huge fucking turbinates, even relative to my already huge fucking head

My good friend Ken took me to the Magic game last night some number of nights ago. It was a great game because we were losing very badly, and then it became very close, and then, right at the end—we won! The classic comeback narrative arc was fulfilled. Sports!

I was reflecting on life the other day, which is a thing I do more often now that I'm firmly in Phase 3 of my evil plan to ride off into the sunset and gradually be forgotten by all of you.

My original plan for this essay would have pulled at the common thread that ties things like game design, derivatives trading, reality shows, and sports betting together. Unfortunately and unsurprisingly, it was taking me too long, and I'm now running out of time in November to give you a recap on what happened in October.

(By the way, don't be surprised if I just send you all a postcard for the December issue. I'm still new at running a monthly newsletter, and I'd prefer not to find out what happens when I fall more than a month behind. Feel free to demand a refund by replying to this message.)

So, anyway, like I said, my actual essay fell apart. Instead, I'm going to share a personal example of how a series of consequential decisions can paradoxically be both productive & rational, while simultaneously being costly & misguided.

I'd do it all again

It all started with one stray piece of unsolicited feedback.