It's been six months since I posted my eulogy for dad. Just re-read it and cried three times. justin.searls.co/mails/2024-12/

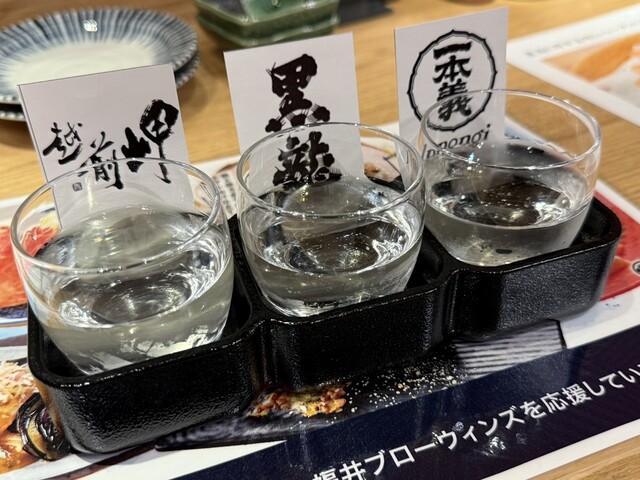

Tabelogged: くずし割烹 ぼんた 個室お二階

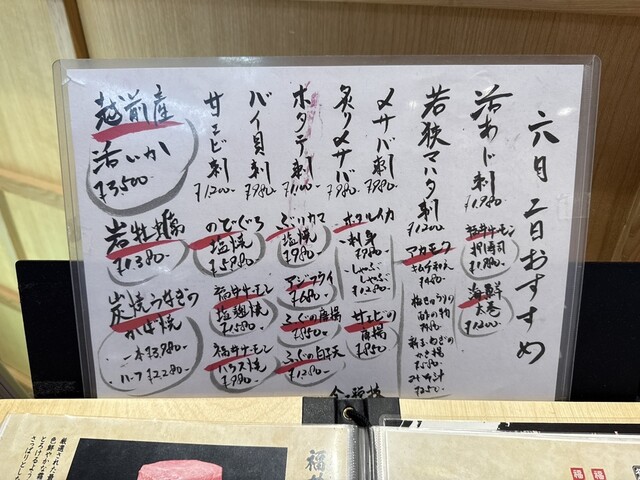

Tabelogged: 魚河岸直営 いけす海鮮 ろ組 くるふ福井駅店

As some of you know, I moved to Orlando in 2020. But it wasn't so much Orlando as Disney World itself, given our home's relative proximity to the parks and the degree to which we're isolated from most of the "Florida stuff" that comes to mind when I tell people I live in Florida.

One of the great joys of where we live is that I've made a variety of fascinating friends who similarly relocated to central Florida with a degree of intentionality, and one of them is Eric Doggett. Eric is a phenomenally talented photographer, artist, and all-around creative. In fact, if you listen to Breaking Change, a big reason it sounds as good as it does is thanks to Eric!

A couple years ago, Eric was admitted into the Disney Fine Art program, and now he officially has some prints for sale. Check out his announcement video:

If you're a Disney fan and you're the art-buying sort, go buy some! I especially love the new Palm Springs motif he's been iterating on most recently.

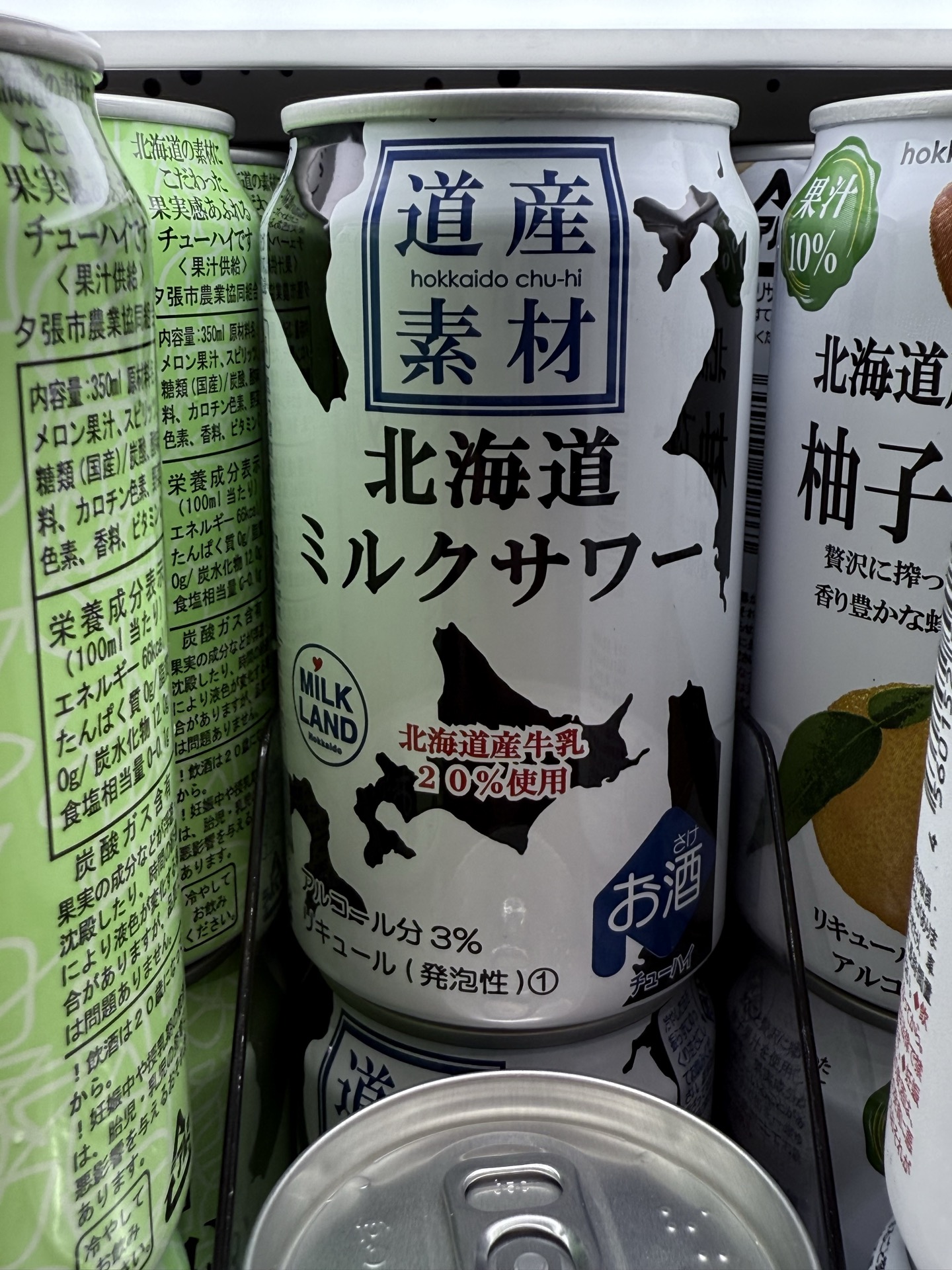

Try this Milk Sour!

An accident of language—the fact that "sour milk" sounds so unappealing—is probably why nobody in America ever considered making a "milk sour", which is just... exactly what it sounds like.

Milk and liquor, together at last.

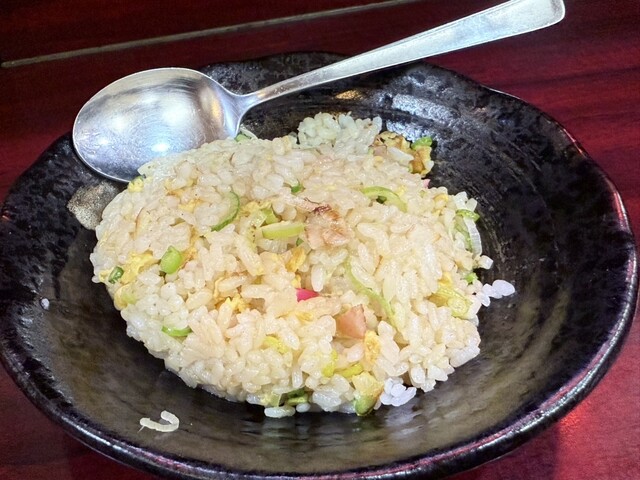

Tabelogged: 焼肉ニューミート

Tabelogged: マルカドール

Why agents are bad pair programmers

LLM agents make bad pairs because they code faster than humans think.

I'll admit, I've had a lot of fun using GitHub Copilot's agent mode in VS Code this month. It's invigorating to watch it effortlessly write a working method on the first try. It's a relief when the agent unblocks me by reaching for a framework API I didn't even know existed. It's motivating to pair with someone even more tirelessly committed to my goal than I am.

In fact, pairing with top LLMs evokes many memories of pairing with top human programmers.

The worst memories.

Memories of my pair grabbing the keyboard and—in total and unhelpful silence—hammering out code faster than I could ever hope to read it. Memories of slowly, inevitably becoming disengaged after expending all my mental energy in a futile attempt to keep up. Memories of my pair hitting a roadblock and finally looking to me for help, only to catch me off guard and without a clue as to what had been going on in the preceding minutes, hours, or days. Memories of gradually realizing my pair had been building the wrong thing all along and then suddenly realizing the task now fell to me to remediate a boatload of incidental complexity in order to hit a deadline.

So yes, pairing with an AI agent can be uncannily similar to pairing with an expert programmer.

The path forward

What should we do instead? Two things:

- The same thing I did with human pair programmers who wanted to take the ball and run with it: I let them have it. In a perfect world, pairing might lead to a better solution, but there's no point in forcing it when both parties aren't bought in. Instead, I'd break the work down into discrete sub-components for my colleague to build independently. I would then review those pieces as pull requests. Translating that advice to LLM-based tools: give up on editor-based agentic pairing in favor of asynchronous workflows like GitHub's new Coding Agent, whose work you can also review via pull request

- Continue to practice pair-programming with your editor, but throttle down from the semi-autonomous "Agent" mode to the turn-based "Edit" or "Ask" modes. You'll go slower, and that's the point. Also, just like pairing with humans, try to establish a rigorously consistent workflow as opposed to only reaching for AI to troubleshoot. I've found that ping-pong pairing with an AI in Edit mode (where the LLM can propose individual edits but you must manually accept them) strikes the best balance between accelerated productivity and continuous quality control

Give people a few more months with agents and I think (hope) others will arrive at similar conclusions about their suitability as pair programmers. My advice to the AI tool-makers would be to introduce features to make pairing with an AI agent more qualitatively similar to pairing with a human. Agentic pair programmers are not inherently bad, but their lightning-fast speed has the unintended consequence of undercutting any opportunity for collaborating with us mere mortals. If an agent were designed to type at a slower pace, pause and discuss periodically, and frankly expect more of us as equal partners, that could make for a hell of a product offering.

Just imagining it now, any of these features would make agent-based pairing much more effective:

- Let users set how many lines-per-minute of code—or words-per-minute of prose—the agent outputs

- Allow users to pause the agent to ask a clarifying question or push back on its direction without derailing the entire activity or train of thought

- Expand beyond the chat metaphor by adding UI primitives that mirror the work to be done. Enable users to pin the current working session to a particular GitHub issue. Integrate a built-in to-do list to tick off before the feature is complete. That sort of thing

- Design agents to act with less self-confidence and more self-doubt. They should frequently stop to converse: validate why we're building this, solicit advice on the best approach, and express concern when we're going in the wrong direction

- Introduce advanced voice chat to better emulate human-to-human pairing, which would allow the user both to keep their eyes on the code (instead of darting back and forth between an editor and a chat sidebar) and to light up the parts of the brain that find mouth-words more engaging than text

Anyway, that's how I see it from where I'm sitting the morning of Friday, May 30th, 2025. Who knows where these tools will be in a week or month or year, but I'm fairly confident you could find worse advice on meeting this moment.

As always, if you have thoughts, e-mail 'em.

It's crane games all the way down

Finally, a crane game where the prize is another crane game.

With any luck this take will be published in the future (my future, your present) automatically, thanks to the diligent efforts of the loyal employees of Searls LLC and as demonstrated in this example repo github.com/searls/static-site-enhancement-concept

Forbidden Button

I have never wanted to press a button more than I want to press this button