You're looking at my e-mail newsletter, Searls of Wisdom, recreated for you here in website form. For the full experience, subscribe and get it delivered to your inbox each month!

Searls of Wisdom for July 2025

I just realized that Christmas in July must have been held somewhere, and I missed it. Damn.

Regardless, the blog was busy since we last checked in:

- There's some Xcode stuff for Apple people, as well as the nostalgia of finding the order confirmation of my very first Mac, a 12" iBook G4

- We got in some good thoughtlording with a software design thinkpiece, an organizational design thinkpiece, and an AI thinkpiece

- Reflections on how bang-on my favorite apocalyptic short story set in 2026 turned out to be

- A couple podcasts, too (1, 2)

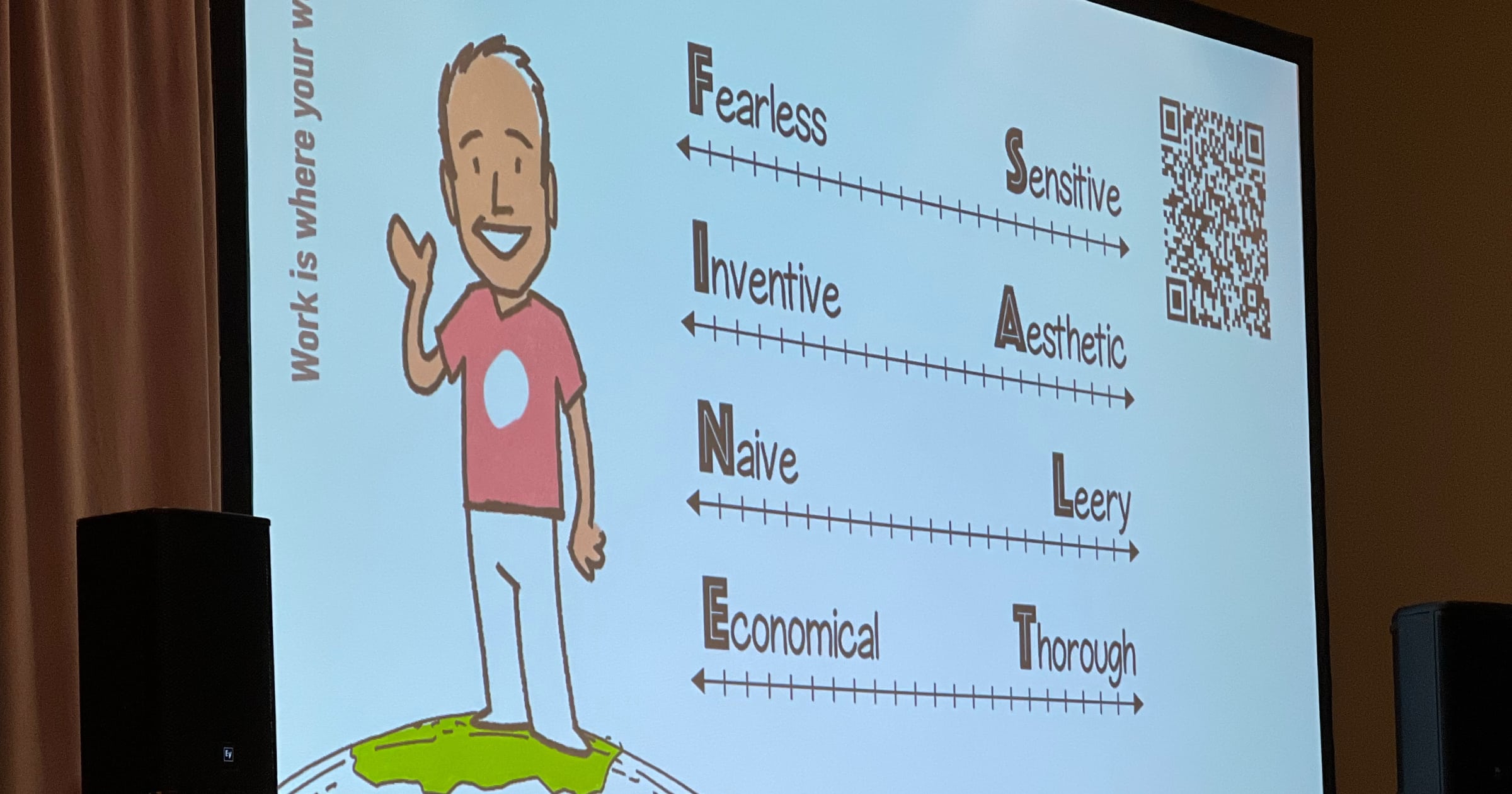

Also since I last wrote you, they held the final RailsConf, an event and community that had a huge impact on my career. I was honored that Aji Slater summarized my 2017 keynote on stage, even though I don't own a single pair of white pants:

As it happens, I've been chewing on a lot of the same themes I discussed back in that How to Program talk, because the current AI-induced industry shakeup we're experiencing has underscored the importance of taking ownership over how we work. And although I didn't plan this in advance, that's kind of exactly the topic I'm writing about today.

Of course, when I talk about work, I mean it in a quite expansive sense. For most intents and purposes, I retired at the end of 2023. I contend that I still do stuff, but increasingly nothing about my day resembles a traditional job. There is, however, one exception: I now have more meetings on my calendar as a retiree than I did as a full-time employee.

Today, I'll share the unlikely story of how my calendar started filling up again and the even unlikelier reality that I'm completely okay with it (happy, even).

There are many different ways to feel about the word "process":

-

Some are indifferent. They show up each day, follow the herd, and are content with checking boxes. If a process wastes time, blurs focus, or causes friction—that's on whoever designed and implemented the process, not them

-

Some are stifled. They have their preferred way of doing things and will judge a process not on its own merits, but as the sum of deviations it takes from their way of doing things. They often opt into flat organizations with a light touch, hoping others will stay out of their way

-

Some are obsessive. Without a clear and comprehensive process in place that covers every conceivable contingency, they fall to pieces. Once they get acclimated, any talk of changing the process—or, God forbid, eliminating it—spikes their blood pressure and triggers a threat response

-

Some are pragmatic. They can thrive with a heavy-handed process or no process at all. What matters is that whatever is expected of them is a good fit for today's problems. What's more, they want a say in the continued evolution of the process itself, just as they would in the maintenance of any other tool on the worksite.

Managing a company that welcomes and tolerates all four of these dispositions would be a complete pain in the ass, and I don't recommend it. The indifferent won't leave unless they win the lotto or you fire them. The stifled can play ball in external-facing roles and at early-stage companies, but will generally be more trouble than they're worth at a larger scale. Obsessives are a bad fit for startups—feeling neglected in the early stages and overwhelmed by reorgs and scaling churn in the middle stages—but are right at home in bureaucratic and staid late-stage companies. One might assume pragmatists can fit in anywhere, but in reality they're the canaries in the coal mine—if your organization doesn't have its shit together, results-oriented people will get bored and go work somewhere that does.

Give me a team made up of nothing but process pragmatists and we can scale horizontally as a flat organization far beyond the point most others would collapse in on themselves. In fact, I have a suspicion that most organizational design memes like "self-organizing", "agile", "lean", and "squads" were initially coined by pragmatists who innovated custom processes for their unique situations. Things went well for them, they wrote a blog post or book about their experience, and then they moved on.

Those books were then bought by obsessives shopping for a reputable off-the-shelf process, and who went on to adopt that process as their ideology despite never really "getting" it. They'd codify and gate-keep the process, organize conferences, conduct trainings, and administer certification programs… before inevitably splintering into distinct religious sects. Because obsessives are the only ones who care so damn much about process, the rest of us are happy to delegate it to them. As a result, we tend to conceive of what process is or can be on the terms of those who have an unhealthy obsession with it. (If you're already bored reading this, thank the world's feckless middle managers—and their projection of false authority masking unresolved anxieties—for ruining "process" for the rest of us.)

If someone gives you a process to follow and doesn't leave room for you to apply it to your particular situation, they're doing both you and themselves a disservice. The only way to ensure a system or process will reliably achieve its desired outcomes is if the people following it deeply understand and buy into how it's supposed to translate their actions into those outcomes. And the best way to foster that understanding and buy-in is for the people executing the process to have a hand in its creation and evolution. Good process design is like an inside joke: you just had to be there.

Sure, there will be constraints the process will have to accommodate—customer demands, industry regulations, inflexible software tools—but there is no escaping it: you're the one who owns how you think through and approach your work. Your brain cannot be outsourced. There's a widespread delusion we can adopt a famous company's "playbook" as a starting point, customize it to our liking, and achieve the same success they did. But a methodology's effectiveness depends on its practitioners' sense of ownership as they continuously adapt it to their unique context. Whatever mechanical steps and procedures emerge are an artifact of the thing, not the thing itself. Adopting some other company's system like Shape Up or Spotify Squads would be like stealing another family's photo album and rewriting your own names into the captions.

But this issue of Searls of Wisdom is not here to tell you how to design and implement custom processes to scale your business. (If you want to pay me to tell you anyway, knock yourself out.) All I'm here to say is that every organization owns their process, that few among us understand this to be part of the job, and that the people excited about process for the sake of process are the last ones we should trust with it.

Connect 4

Okay, we are in desperate need of a concrete example. I'd like to tell the story of a process that was designed to address real problems, how it was iterated and improved upon, and why it's not for you.

Today, I serve as chairman of a multi-national conglomerate of several businesses. Each day, I toil away in a co-working space (my house) alongside the CEO of one of our portfolio companies (my wife, Becky).

As is right and good, we began our individual endeavors without any preconceived process. We showed up, we did our work, and then things would go as well or as poorly as they were going to. We didn't impose any structure on ourselves.

A few months in, it became clear we were operating on wildly different wavelengths. Working different hours. Frequently interrupting each other. Stepping on each other's toes. She wanted more connection throughout the day. I wanted more coordination to ensure things got done.

We initially tried to solve this ad hoc by simply showing up to work differently. I attempted a mindset shift called, "be a nice person," which lasted for a day or two. Since that didn't work, I leaned on what my career had taught me: if good intentions and sheer force of will aren't enough, it's likely a sign the underlying problem is systemic. And systemic problems demand systemic solutions.

Iteration 1: a recurring calendar event

So we spun up our first process: every morning at 7:30, we'd come downstairs for "Coffee Time." We'd sync our schedules by starting the day together, each pouring a coffee and sitting by each other in the living room or out on the lanai.

Coffee Time successfully aligned our working hours, but it created all-new problems. It wasn't a meeting so much as a scheduled coexistence, so I'd work on my computer while Becky would read. One of us would try to strike up conversation or discuss plans for the day, which the other would experience as an interruption. Any given instance of Coffee Time might last 5 minutes or run for 2 hours.

It almost always ended with one or both of us feeling mildly irritated.

Iteration 2: ground rules

Since Coffee Time clearly needed more structure to achieve its desired outcome, we added a constraint: no devices. We'd sit our asses down at the appointed time and place, sip our coffee, and be forced to talk to each other.

One member of our team is an optimistic, energetic morning person and loved this process tweak.

Others, who shall remain nameless, struggle to engage in conversation first thing in the morning and that's why this change fucking sucked.

See, I get my best creative work done right after waking up, before something—like freeform conversation—can derail me and poison my day. As a result, Coffee Time represented a high-wire act of my own design: one wrong move and I might lose a whole day's productivity.

This misalignment frequently manifested in conflict. Becky sought unhurried and relaxed connection. I sought to get it over with ASAP so I could go back to my work. We gradually stopped showing up. Coffee Time went the way of so many recurring calendar events: nobody bothering to attend but nobody with the courage to delete it.

Iteration 3: 🔥🔥🔥

The Coffee Time calendar event just sat there for literal months. I lost track of how many times my watch buzzed only for me to ignore it.

When you lose faith in a process you helped establish, it's a special kind of demoralizing. I felt a tinge of shame every time the calendar notification popped up. The event's ongoing existence crowded out any space for a better solution to emerge.

Most people lack the courage to discard pre-existing documents, policies, and processes. Getting rid of practices that everyone agrees are self-defeating or even harmful is nevertheless unusual. When we talk about businesses being slow and inflexible in the face of change, we often think of big companies—but the problem is really with old companies (and most big companies just happen to also be old). The longer they've been in business, the more layers of process and policy sediment pile up. The people who were in the room then aren't in the room now, so past decisions are treated by today's people as untouchable dogma. And unless periodic reset & renewal is reinforced somehow, the institution will gradually calcify and become vulnerable.

Anyway, I lack such inhibitions, so I deleted the Coffee Time event one day. Surely, there existed some better way of cohabiworking, but an unstructured appointment nobody shows up for probably wasn't the answer.

Iteration 4: Structure

Literally the day after I deleted Coffee Time, I had an idea.

I pitched a new meeting: "Connect 4." It would be designed to meet both of our needs. Becky wanted to establish connection and kick off each morning in harmony with one another. I wanted to ensure we coordinated our activities and had the ability to hold one another accountable. It would also give us an opportunity to offer each other our support, whatever that might look like from day to day.

I scribbled four quadrants onto a legal pad and titled it "Connect 4". Each morning, we would take turns, each sharing three things:

- Biggest feel. Name one overriding emotional or physiological feeling. Let the other know what version of yourself they're working with today

- Biggest goal. If you could accomplish just one thing, what would it be? When you look back, what do you want today to be remembered for?

- Biggest want or need. We're not just here to get shit done—we're here in pursuit of a life well-lived. What does that look like today?

After reflecting and sharing our answers to the above questions, there was one last step. (I needed a fourth thing so I could call the meeting "Connect 4".) So, after we'd both had our turns to speak, we would pose a question to the other: "What can I do to support you today?" It was important we offer support by way of a question, as opposed to guessing what the other needed (which would be presumptive) or directly stating the support we wanted (which could be interpreted as an imposition). If I ask Becky how I can support her and however she answers isn't something I'm thrilled about doing, that I asked for it makes it more likely I'll follow through. Little touches like this are a great example of structure reflecting purpose.

That's it. Three quick things plus one question. Achievable in ten minutes. We both get our needs met.

I resisted introducing something like Connect 4 for over a year, because it felt stupid to kick off my retirement by signing up to do daily standup meetings with my wife. But once we got going, it didn't feel that way at all. Because the process solved real problems that we'd actually been struggling with, there wasn't anything to complain about.

Iteration 5: the ceremony

Connect 4 immediately proved more valuable than our previous attempts at starting each day on the right foot, but it also would not have materialized without them. It's important not to be too hard on yourself if your initial solution fails to solve the problem—something can only be improved once it actually exists.

Still, Connect 4 wasn't perfect:

- Originally, Connect 4 was only scheduled on weekdays, but we gradually found the days we didn't sync suffered for it, so now we do it seven days a week

- We'd sometimes derail things by going on long tangents, so we began to (kindly) defer those conversations until we'd gotten through our Connect 4 updates

- Conversation regularly unearthed deeper issues that warranted more time than a quick check-in would allow, so we began scheduling ad hoc follow-up meetings as needed

There was one other lingering problem that persisted for a few months before we identified and addressed it. See, despite having a scheduled start time, the reality of being two self-employed people working from home meant it wasn't uncommon for one of us to get into flow and fail to show up on time. This, in turn required the other to go and collect the other, interrupting them. And when one person has to call the meeting, they become the de facto person to run the meeting. This can introduce or reinforce a vertical dynamic, which is counterproductive to building a sense of mutual respect and commitment.

To solve for this—and one wonders whether this is how church bells got invented—I took a sound bite of the Family Mart chime and configured HomeKit to automatically play it at 8:30 AM in every room of the house. This way, neither of us has to call the meeting—the meeting calls itself. We separately stop what we're doing and attend it of our own volition, as peers.

Some will read the above and think it's too insignificant a thing to bother with, but people fail to realize this sort of reaction is what leads to our lives feeling so cluttered and overwhelming. Insignificant things pile up. If you choose to ignore a small pebble in your shoe, no one's going to award you a prize for learning to live with it. Not letting life's little irritants bother you may sound laudable, but if you forget about that pebble you might later fail to identify it as the cause of your postural problems, or your joint pain, or your short temper.

Don't make the mistake of equating the apparent size of a problem with its potential impact when assessing whether it's worth taking the time to fix it.

You're the one you're waiting for

Connect 4 is just one of dozens of goofy practices Becky and I have created to draw out the best versions of ourselves. We name each of our customs. We sing jingles. We have secret handshakes. We reflect on what's working and what isn't. We make tweaks. We aren't afraid to let go of any of our rituals once they're no longer useful.

Why do we bother taking the time to do all this? Because it never occurred to us to invite some third person to optimize our marriage for us. That just sounds ridiculous.

And yet, the vast majority of employees expect their employer to optimize their workflow for them. That sounds pretty ridiculous, too, if you ask me.

And sure, I could write a book on all the things Becky and I do to live our best lives, but this one example is all you're getting. I am aware that all it would take is to give each practice its own chapter—brand it with a name, explain what it solves, how it's done, and why it works. I could earn money and notoriety by pitching our system as a framework to building a happier marriage, or achieving work-life harmony, or some other bullshit. But that would just be prescribing yet another process for others to follow. And even if I was offering genuinely helpful advice, it would only further prevent people from figuring out for themselves that the path to greatness is not a paved road, but a blazed trail. There's nothing of value to be gained by blithely retracing someone else's steps.

If taking ownership of the systems that govern how you think through problems and interact with others seems out of reach, it shouldn't. Humans tend to live and work in pretty small groups—it's not unreasonable for everyone to have a say. I've witnessed families and teams alike who agreed to make decisions by consensus, who expect everyone to propose improvements, and who celebrate doing the things nobody asked for. It's not hard to live this way, but it won't magically happen on its own.

Following a process without continuously improving it is like driving a car without touching the steering wheel. The only person staring down the road ahead is you. That makes you the best person to figure out how to get wherever you're going.