You're looking at my e-mail newsletter, Searls of Wisdom, recreated for you here in website form. For the full experience, subscribe and get it delivered to your inbox each month!

Searls of Wisdom for April 2024

We kicked April off right around here with a stay at the new Evermore resort's Conrad hotel, which saw fit to include yet another upscale tiki bar in a part of town that contains an order of magnitude more tiki bars than thai restaurants. And five times more tiki bars than pharmacies. Roughly as many tiki bars as schools, judging by a quick search. Anyway, here's me drinking an Oaxaca Colada out of a ceramic conch shell:

Not too much to report this month that I didn't already cover on my web site, as I was mostly heads-down writing software.

Oh, by the way, to all the folks who kindly wrote in to express sympathy about the back pain that I documented here last month: thank you. It was entirely uncalled for (as in, I did not call for it), but I appreciate the sentiment. For what it's worth, I got in to see my physical therapist and she patiently listened to me ramble about the dozen theories I'd been crafting before simply asking, "are you doing the hamstring stretches I showed you two years ago?" At which point, I melted into a pile of humiliated goo and slid away, escaping under the door.

Anyway, stretching my hamstrings every day is helping a lot. God, I hate doing them, though.

April was also defined by the various preparations needed for what's shaping up to be another epic Japan trip. (Incidentally, this is also what consumed a good chunk of last April.) After going to RubyKaigi as a foreign correspondent for Test Double, I've decided to return in a slightly more low-key fashion. Oh, and this time Becky's joining me!

After the conference, I'm hoping to spend a couple weeks wandering heretofore unexplored (by me) regions of the country on a solo language-learning and research expedition. To assist in documenting all the places I'll go, I added a mapping feature to my site that I call Spots.

As I check items off my packing list, I re-installed and logged into several of the apps I use whenever I'm in Japan. Switching my phone to my Japanese Apple ID for this purpose has become something of an annual ritual of mild frustration that nevertheless leaves me ponderous. Why does everyday life in Japan require a full home screen of only-available-in-the-Japanese-App-Store apps? And if we were to compare them to their counterparts in the West, what might they teach us?

When I first signed up for a study abroad program nearly 20 years ago, it was in large part because Japan seemed like such a radical departure from my upbringing in the states. When I took an elective on post-war Japanese industrial design, I was repeatedly awestruck by the number of tools and appliances that solved common problems in ways I hadn't seen before. That so many things are designed and produced independently in Japan made me realize how many facets of life I'd assumed to be constant were in fact variable. Knobs that twisted left when they "should" have twisted right. The tea kettle whose fully-concealed cord resulted in my not realizing it was electric and subsequently melting it over my gas range. The countless bathtub drains whose basic operation escaped me, leading to my checking out from more than one hotel with a tub full of water. But one thing I hadn't bargained for was the degree to which this profound differentness would also apply to Japanese software design.

Japan produces a lot of software intended primarily (if not exclusively) for domestic consumption. For almost every major function of our lives that's mediated by a popular app, it's likely some other app you've never heard of dominates the same market in Japan. The fact these apps often emerged in relative isolation provides a sort of natural experiment, offering us the opportunity to question features we thought were essential and appreciate alternate approaches we might not have arrived at ourselves.

In case it might whet your appetite for exploring these differences, today I'm going to give a quick run-down of a few of my favorite Japanese apps below.

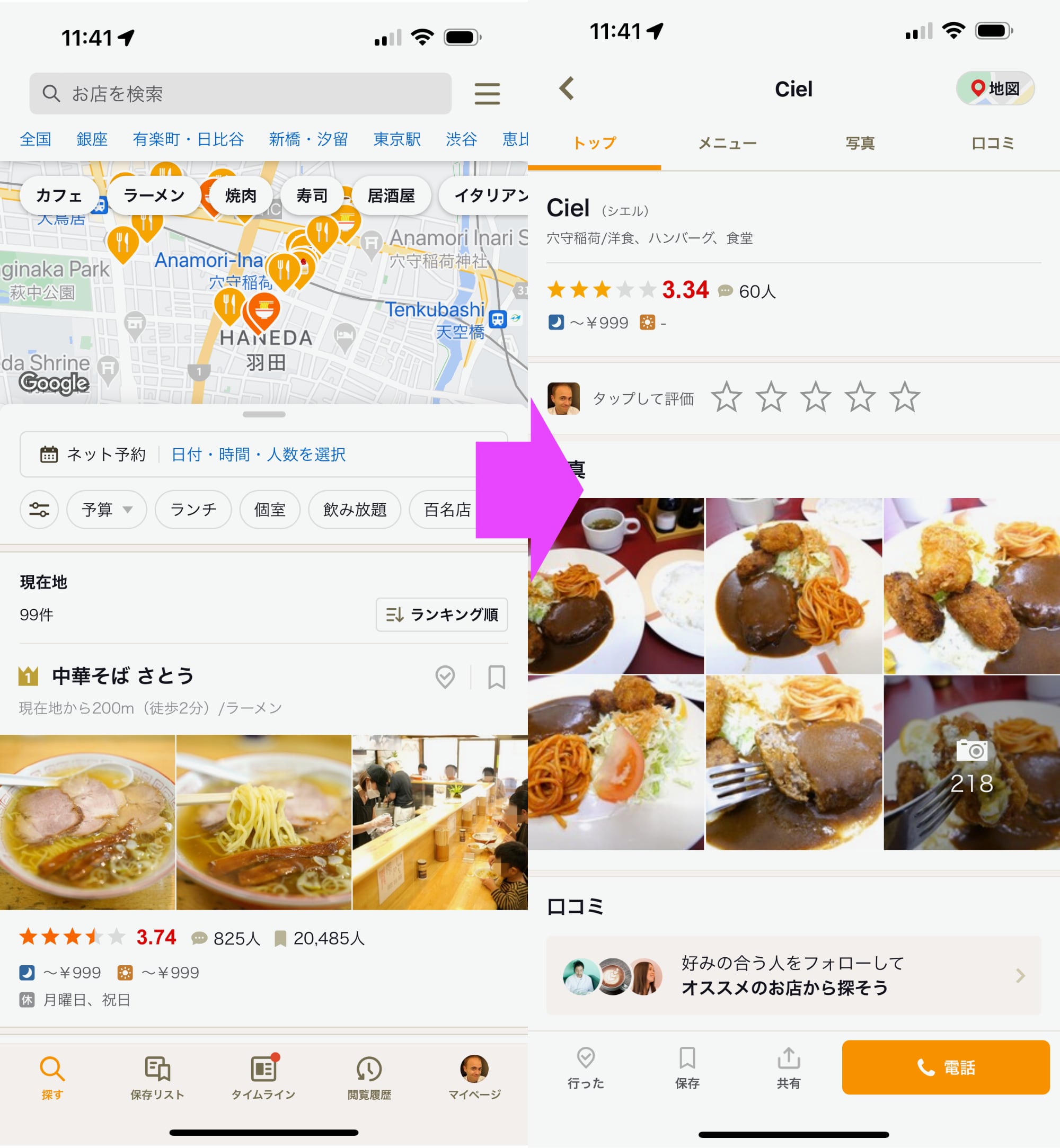

Tabelog

Compare to: Yelp

Founded: 2005

Revenue: $330M (est.)

Commercials: Often just tell you how to use the app

App: 食べログ

If you travel Japan and rely on English-language apps to search for restaurants, you're likely to have an odd experience. You might find that Yelp doesn't have a single review of a single restaurant in whatever city you're visiting. Or that your maps app is only surfacing Tripadvisor reviews posted by foreign tourists. This can be useful if the question you're trying to answer is, "where do foreigners like to eat?" but much less so if your objective is to find hidden gems off the beaten path.

Instead, the real foodies all rely on Tabelog. Followed by HotPepper. Followed by Gurunavi.

My favorite thing about Tabelog is the unbelievably brutal review scores. Like Yelp, Tabelog's review scale is 1 to 5, measured in 0.1 increments. Unlike Yelp, a score of 3.0 means "meets expectations," as opposed to "vaguely disappointing." Tabelog reviewers are generally reticent to hand out reviews of 4.0 or higher for anything less than incredible culinary experiences. As a result, aggregate reviews tend to cluster between 2.9 and 3.5, and to find a restaurant with a higher rating is truly exceptional. I've sometimes disappointed fellow travelers when I excitedly tell them I booked a restaurant with a 3.7 rating, because Yelp's relatively-inflated scores have anchored Americans to expect ratings of 4.5 & up. In reality, though, it's Yelp's reviews that are useless, because they fail to discriminate quality sufficiently—when every restaurant is a 5.0, no restaurant is.

Apart from advertisements, coupon promotions, reservations, and paid bookings, Tabelog also generates revenue through a premium subscription offering. Tabelog Premium, which costs a mere ¥400 per month via In-App Purchase, includes an indispensible service: sorting restaurants by their review ranking. This is absolutely shocking to most people when they hear it. Foreigners are shocked, because our entire conception of a review site is to find the highest-rated stuff, so the idea that the primary function of an app would be hidden behind a paywall seems absurd. Locals are shocked, because most of them have no clue what Tabelog Premium even does, and as a result are routinely impressed by my ability to find such obscure and delicious restaurants everywhere in the country.

In fact, Tabelog's design decision to gate ranked ordering of restaurants behind a paywall has undeniably safeguarded one of the most important qualities of Japan's restaurant industry: low-volume craftsmanship. As a country that's often obsessed with chasing whatever's popular, rank-sorting restaurants for every user would result in top-rated restaurants—which are often extremely small and only designed to serve a hundred patrons per day—being swarmed by a crush of nonstop traffic. Many Japanese restaurateurs aren't seeking to maximize financial success or scale up by opening additional restaurants. Rather, many are in it for the "kodawari," or pursuit of perfection in their craft. Over the course of years, they refine every step in their process. To illustrate how foreign this concept can be, many shop owners choose to treat price as a fixed constraint as opposed to something to be maximized, which is why a majority of the top ten bowls of ramen in the country can still be had for less than $10.

Tabelog had a short-lived English-language app designed for the Western world, but it's long since been shuttered. The Japanese app isn't localized into English, either, so navigating it would be difficult for anyone not able to read Japanese at an intermediate level. Fortunately, their web site (which is frequently linked to by Apple Maps) is localized and Safari's built-in translation tools should be enough to give you the gist. Especially crucial are Tabelog's photos of restaurants' exteriors, because GPS is of limited use when locating small restaurants tucked away in crowded alleys or up four-story walkups.

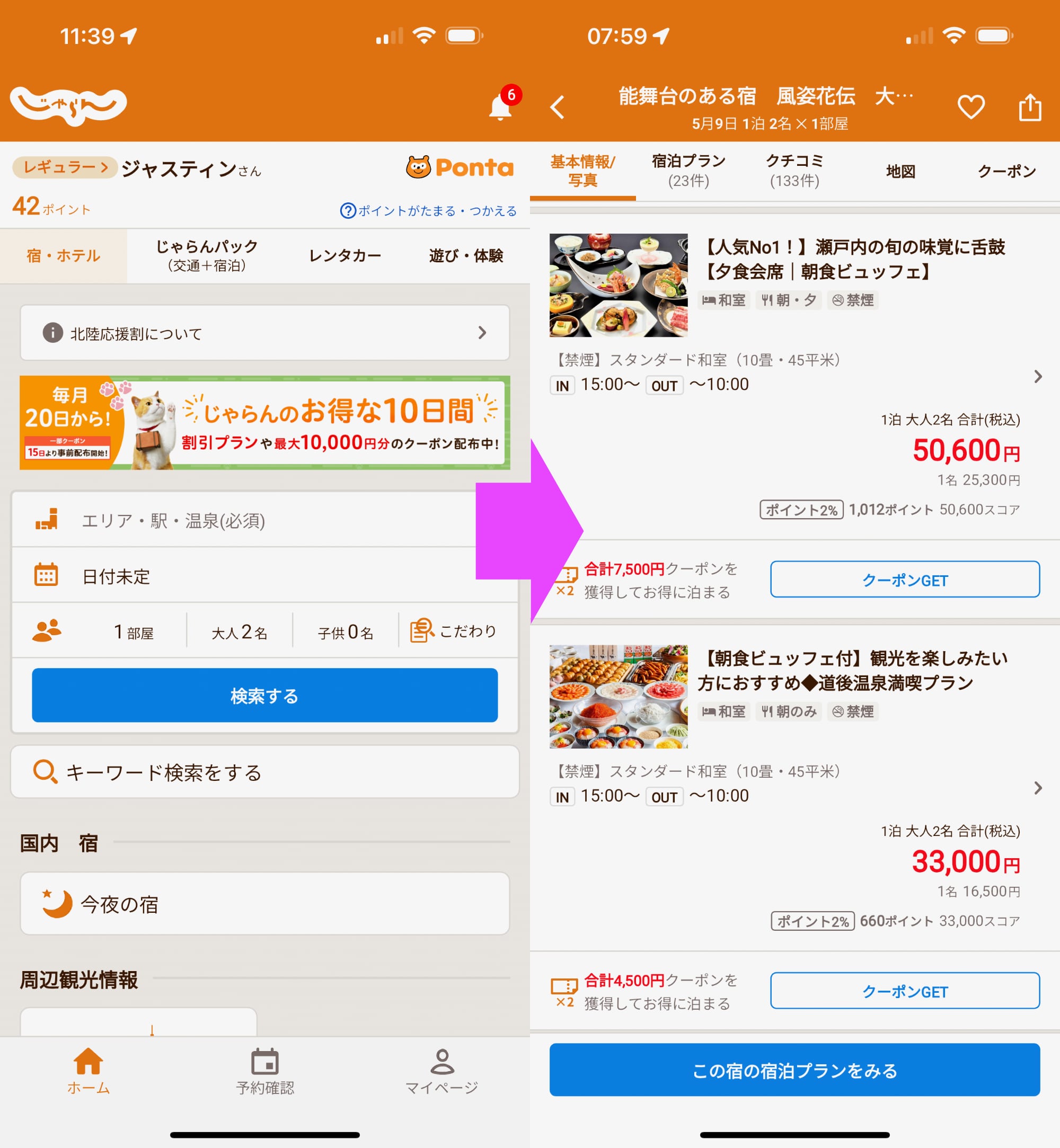

Jalan

Compare to: Expedia

Founded: 1991

Revenue: $200-400M (est.)

Commercials: Usually feature nyalan, the Jalan cat

App: じゃらん

Before the yen's precipitous decline in 2020, Jalan mostly stood out as a domestic travel booking site that catered to a Japanese audience that tended to look abroad when considering how to spend their scarce time off work. As a result, Jalan's design plays up Japanese cultural traditions more than it otherwise might. One way Jalan promotes domestic travel is by giving onsen hot spring resorts and traditional ryokan top-billing in the app's navigation, as opposed to burying them alongside other search results.

Because Jalan was designed for the Japanese market, its UI embeds several important cultural aspects of hotel travel you won't find elsewhere:

- The primacy of dining: rather than sorting a hotel's rates by room type, varying meal plans are the UI's first order concern. It's not uncommon for the smallest hotel room and fanciest kaiseki dinner to cost more than a hotel's largest suite when paired with its cheapest dining option

- Pay per guest: unlike the West, where the price of a hotel room is fixed regardless the number of humans sleeping in it, hotel rates in Japan are often priced per guest per night. In fact, it's sometimes the case that booking a single room for three people will work out to the same total price as booking a separate room for everyone. Per-guest pricing is rarely surfaced accurately on international listings and occasionally necessitates significant price adjustments at check-in (which is frustrating for everyone), but because Jalan was designed with this custom in mind, every page in its reservation process makes clear the price for each adult/senior/child in your party

- Gendered pricing: I've lost track of how many times I've excitedly found an eye-poppingly cheap rate on Jalan only to read the plan's summary and find it was a "girl's trip" price. More than once, I've imagined what would happen if I booked a girl's trip for myself and feigned obliviousness at the front desk. Regardless of rate plan, users are required to specify a count of who is staying in each room by (binary) gender before finalizing a reservation, something that's hard to imagine being asked for in the US at this point

Of course, now that the yen is quite weak and most international destinations have experienced significant post-pandemic inflation, Japanese travelers have been left with little choice but to stay close to home, resulting in a surge of domestic travel in recent years. Reopening Japan's visa waiver program in 2022 complicated matters, however, as the country is now experiencing an unprecedented number of international tourists as well—travelers who are flush with cash and driving up the prices of scarce luxury hotels as they crowd tourism hotspots like Kyoto.

This dynamic, in which most Japanese can only afford to travel domestically at a time when international guests are pricing them out of the most popular domestic destinations, has put Jalan's focus on cultural heritage and Showa-era nostalgia into stark relief. Because Jalan's foreign-language site is extremely limited (listing only hotels that opt-in by certifying their English-speaking staff can accommodate foreign guests), and because a huge swath of Japanese hotel inventory isn't listed on Booking, Expedia, and other international hotel aggregators, Jalan offers Japanese-speaking tourists a sort of pricing and inventory refuge—especially in harder-to-reach rural destinations.

That was a dense paragraph, so here's an example. If I search Booking for hotels in Matsuyama, Ehime prefecture, I get 60 results with an average nightly rate of $150. When I searched the same dates on Jalan I got over twice as many results, including many hotels at either pricing extreme that aren't listed on Booking. On the low end, some rooms on Jalan were as little as $16 per night while offering coupons that knocked an additional 20% off the price. On the high end, several very fancy-looking ryokan and onsen resorts appear not to be listed on Booking at all, presumably preferring to cater to Japanese guests. (Because foreign guests are less likely to respect Japanese customs and tend to be more disruptive, I suspect there is a sizable market for resort hotels that don't go out of their way to make themselves known to international visitors.)

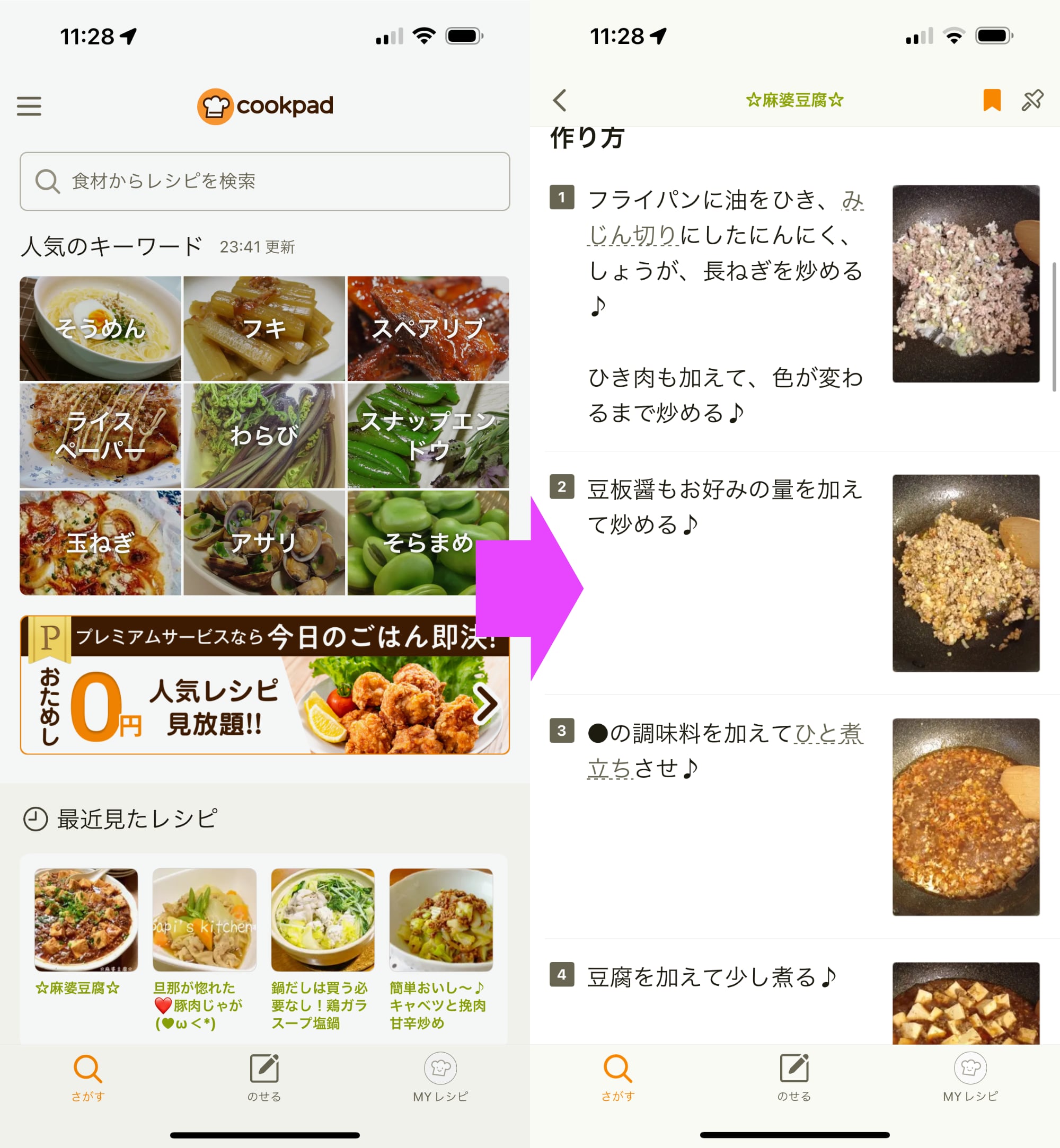

Cookpad

Compare to: Epicurious

Founded: 1997

Revenue: $75M

Commercials: Encourage people to try their hand at cooking

App: クックパッド

If you've heard of Cookpad in the West, odds are it's because of Cookpad's status as Japan's best-known Ruby on Rails application, having incubated a number of important innovations in Ruby and Rails over the years. But the service Cookpad provides is culturally significant in its own right, as it offers millions of recipes to both aspiring and experienced home cooks alike.

When we moved to a Japanese suburb in the summer of 2019, I understood my role as house husband would likely require me to visit the local grocery store several times a week. What I failed to grasp, however, was that Japanese supermarkets would be organized completely differently than they are in America (and why shouldn't they be?). Worse, as soon as I felt like I got a handle on where to find everything, the season would change and all of the ingredients I was finally comfortable cooking with would be replaced by whatever was in season ("shun" / 旬) that month. Japan proudly experiences all four seasons (and it's important enough to have earned a two-syllable word in "shiki" / 四季), but if you were to demarcate seasons by when produce items cycle in and out of store aisles, you'd be forgiven for thinking the country has 10 or more distinct seasons.

Thanks to this rapid seasonal turnover, I found myself frequently holding an unfamiliar vegetable and asking myself things like, "what the hell am I supposed to do with hakusai cabbage?" For that purpose, Cookpad proved essential. Whenever you open the app, you're greeted by top-ranked recipes that reflect the same local and seasonal ingredients you'll find in the store. At least once a week I'd try to learn a new recipe, and (despite the language barrier) Cookpad made home cooking accessible to me in a way that America's celebrity-centric cooking shows and SEO-riddled recipe blog posts never did.

Of course, Cookpad wasn't made for me, which suggests I'm not the only one who benefits from its help navigating Japanese cuisine. Japan's traditional homemaker role comes with (unfairly) high expectations with respect to the quality and variety of breakfasts, bento lunches, and dinners that are prepared for one's family, and as Japan's declining population is gradually pulled towards its three major population centers, those homemakers often lack the support system to meet those expectations on their own. In that context, the extraordinary popularity of Cookpad's educational and community features make a lot more sense.

Thanks for attending my App Store revue

These were just a few of the apps that come to mind that have managed to outperform (if not vanquish) their foreign competitors. I'm sure I could point to interesting details in Demaecan's approach to food delivery, or GO for taxi dispatch, or PayPay for mobile payments, but I suspect you get the broader point by now.

I'm sure for some of you, my haphazard summaries of these apps will have seemed like a waste of time, but I can't contain my fascination with how culture is expressed through design and technology. I'm grateful there are at least a few countries that are stubborn and idiosyncratic enough to resist the hegemony of US tech companies, and Japan might be chief among them.

Anyway, now that I've got my apps installed and a data eSIM (referral link) set up, I'd better get finished packing. If you'll be at RubyKaigi next month in Okinawa, drop me a line and let me know!

Oh, and don't forget to stretch those hammies!