You're looking at my e-mail newsletter, Searls of Wisdom, recreated for you here in website form. For the full experience, subscribe and get it delivered to your inbox each month!

Searls of Wisdom for October 2023

This month in Disney World living, my brother Jeremy and I got to meet Aaron Paul and Brian Cranston at an event promoting their Dos Hombres mezcal:

I have no more to say about that. Life here is silly.

Respecting your limits

"If you can't do the deal, don't do the deal."

This was the first piece of after-hours advice I received as a "road warrior" consultant in 2007. I was traveling cross-country every week to work on-site for my client in order to—let's face it—mostly sit by myself in a cubicle at a computer.

Hold up a minute. "If you can't do the deal, don't do the deal"? What the hell is that supposed to mean? I was confused as well at the time, and even now I can't say I'm totally sure how to parse it. But this turn of phrase, or my years-long struggle to understand it, has had a major impact on how I decide when to commit and when to take a pass.

See, the person who told me this didn't work for my client. He was a colleague from my consultancy, the account executive on the project, and the congenial ringleader of the 8-or-so of us traveling consultants living out of the same hotel. And he didn't tell me this at work. No, we were just leaving a 4-hour, martini-soaked meal at a high-end steakhouse and discussing which bar to hit next. It was already way past my bedtime and I had to be at the client site early the next morning. But as the new guy, I was feeling self-imposed social pressure to muscle through and keep up with these guys. I didn't feel safe ducking out early on my own.

My account exec could tell.

"If you can't do the deal, don't do the deal," he told me in a relaxed, sing-songy voice as he spread his arms wide.

What followed was a dramatic retelling of past adventures, in which stories of triumph ("we left the club at 6 AM, picked up a fresh suit from the dry cleaner, and gave the Q3 financial presentation to a packed house at 9 AM") and tragedy ("he didn't show up until 11 AM the next day, bloodshot and haggard, and the client put him on the next plane home") were regaled right there in the Del Frisco's parking lot.

These stories were his way of saying I should ignore everyone else and operate based on my own limits. If I can hang until the after-after-after party and still show up on time in a freshly-starched shirt and pleated khakis with the mental clarity to put in my best work, then let's go. If I can't, then here's an aspirin and a taxi to take me back to the Embassy Suites.

My default wiring is a bit paradoxical: I have very little capacity for socializing, but it's paired with such an outsized need for others' validation that I can't stand the idea of missing out. As a result, I spent way too many nights of that six-month project eating more than I should, drinking more than I should, and sleeping far too little. It was as if I'd been caught smoking as a kid and then forced to smoke an entire carton of cigarettes. Having a seemingly-unlimited expense account (and nowhere to go but a lonely hotel room) eventually made me come to grips with my own limitations. I was gaining weight. I was shedding hair. I developed weird health issues. I visited my doctor so many times he told me he couldn't help until I changed my lifestyle.

It was a bit of a wake up call, but it was hardly my come-to-Jesus moment. I hadn't hit rock bottom. I just learned the hard way when I could and couldn't do the deal. In my final weeks on the engagement, I was finally starting to self-regulate in an environment of overabundance: skip the breakfast buffet, go for a jog, join the complimentary happy hour after work, order fish at dinner, and fall asleep watching HBO in lieu of the late-night poker game.

In the years that followed, a surprising number of my personal and professional struggles have brought me back to the same advice: "if you can't do the deal, don't do the deal." It's why I started saying no to speaking at so many conferences when they were getting in the way of the rest of my life. It's why I can finally admit I don't want to hang out when it's clear that forcing it would make myself (and others) miserable in the process. It's why I feel zero regret turning down fabulously-lucrative business opportunities when they would require more of me than I'm prepared to give.

As I close in on three years since moving to Florida, my mind keeps returning to the fact that my primary goal in moving here was to gradually ween myself off the unhealthy tendencies that had resulted from having made "yes" my default answer to so many things I never really wanted to do. My career put me face-to-face with countless tech executives who had more money than they could ever hope to spend, who had just sold their startup for a gazillion dollars, and who were nevertheless already working 80 hours a week on their next thing. They each intellectually knew that money was merely a means to an ends, but the mystique of capitalism depends on its being an unwinnable game. Striving for more is what got them this far, and there will always be more for them to strive for.

That's why I count myself fortunate to have spent time with so many accomplished people relatively early on in life. I saw firsthand the toll that reflexively leaning into every opportunity could take on the lives of people capable of seemingly anything except acknowledging their own limitations. Broken marriages. Health problems. Regret.

It's what spurred me over the last few years to start saying no: I can't do the deal.

And the most surprising, delightful thing happened. Saying no to the things I'd spent years saying yes to has opened the door to countless more opportunities I didn't even realize I'd been implicitly rejecting all this time. Dormant friendships. Suppressed curiosities. Novel challenges.

As is so often the case, the lack of confidence that led me to say yes to everyone was only restored when I gained the courage to start telling them no. Come to think of it, I feel as happy and self-assured today as I have at any point in my life. (And that's counting my early 20's, when my under-developed prefrontal cortex had me convinced I was irresistibly sexy and very likely invincible.)

Take a minute. Is there a deal you're signed up for that you need to admit you can't do? With so many people in my life stretching themselves beyond all reasonable limits, I have to think everyone has a deal or two they ought to walk away from.

There's another deal I can't do

Speaking of things I need to admit I can't do anymore: feed-based, notification-driven social media.

(And by notification-driven, I don't mean push notifications. I mean any service that depends on users to generate free content by tapping into the human need for social validation by surfacing how many impressions, likes, or comments their content receives.)

To make a long story short, my 15-year experience with Twitter did something to my brain and now I'm an addict. I am in recovery, but occasionally I slip. I fall into my old habit of pulling-to-refresh to see how many people are liking what I have to say. Throughout my day, whenever I think an uncomfortable thought or get stuck working on a hard problem, I am overwhelmed by a compulsion to check whatever app or website might offer me a new reply or like. (Even e-mail! Twitter made me addicted to e-mail and I'll never forgive Jack Dorsey for it.)

There may come a day when enough time has passed and I'll have healed and I won't be an addict anymore, but the platform holders may sooner do the job for me. Ten years from now, maybe Zuck will replace his need for human creators with generative AI to drive the addicts he really cares about: the content-consuming eyeballs that ingest ads. Who knows. Until then, I can't deal with trying to police and moderate my access to social media when its presence has become the single biggest distraction and emotional drain in my life.

That's why, for the last year, I've been investing time into the design and functionality of my personal web site. My goal? To be freed of my life as a digital vagrant. To no longer post my work across a diaspora of platforms that effectively own my contributions, determine who they reach, and influence how I feel about myself. Instead, I plan to post as much as I can directly to justin.searls.co and automatically broadcast that content elsewhere.

It started with the idea that each social network was at its best when it optimized for a single type of media (Twitter for text, Instagram for Photos, etc.). So I designed a separate kind of post for each of the ways I express myself online. If you visit my site, you'll see them spelled out on the sidebar:

- 📄 Posts: long-form blog posts

- 🔗 Links: commentary about other stuff on the Internet

- 🔥 Takes: shower thoughts and ideas I feel compelled to emit

- 📸 Shots: photos of cocktails and screenshots of software bugs

- 📺 Tubes: videos and screencasts

Of course, posting a bunch of content to a website doesn't do much good if nobody sees it. And since it seems people can no longer be sussed into subscribing to RSS/Atom feeds, I decided to start syndicating indirectly to Mastodon and Instagram. As of last week, my Mastodon account is a fully-automated wall of links to my site's main feed. And as of this week, my Instagram account is cross-posting all my photo posts. (I have since learned this means I have joined the POSSE by Publishing (my) Own Site, Syndicating Elsewhere.)

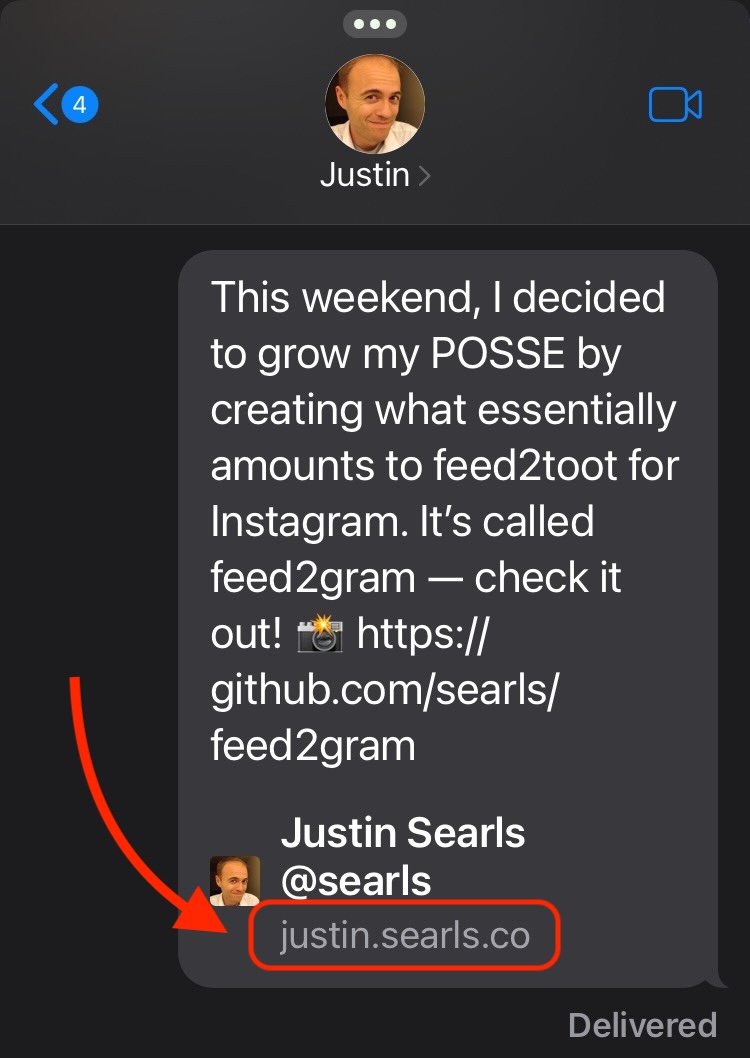

Weirdly, none of the above was enough for me to kick the habit of posting to Mastodon. This may sound stupid, but almost every time I tweet or toot something, I text it directly to a few friends I think might like it. The fact that my short-form blog posts looked worse than my tweets and toots—which render a pleasant full-text preview—rankled me so much that I'd end up bypassing my site and posting directly to Mastodon—just for the side effect of the superior iMessage experience. So I figured out how to make my site do that too:

And with that final building block in place, my year-long project to wrest control of my content (and my attention) from social networks was complete.

For what it's worth, I would love for everyone else to be able to quit posting to social media and start blogging, but the amount of custom software I had to write to accomplish this all would put it out of reach for most people:

- I contorted the Hugo static site generator beyond all recognition to juggle this many kinds of content at once

- To reduce friction, I constructed a menagerie of Shortcuts to quickly share links, photos, and takes directly from my iPhone, iPad, and Mac

- To cross-post to Mastodon, I installed Docker on my Synology to get feed2toot running continuously

- To cross-post photos to Instagram, I learned Facebook's Graph API well enough to write my own program named feed2gram

- To make my takes render like tweets in iMessage, I had to reverse engineer the HTML Apple was searching for to detect Mastodon instances

(By the way, I haven't figured out an economical and low-effort way to host videos without a platform like YouTube. I'm open to suggestions, though, especially if there's a way I might automatically syndicate them to YouTube.)

What's next? I'm not sure, but I can already tell you that I feel great about this. I am suddenly way more concerned about clarifying my thoughts and finding my voice than I am about feeding the algorithm and engaging others, and that can't be a bad thing. I'm noodling over ideas about what to do about video. I keep kicking around the idea of starting a podcast. I'm also trying to imagine how I might help others make a similar migration away from publishing to social networks and toward platforms that offer them more control. (Would you be interested in doing this? Mash that reply button and let me know!)

Also, and this is incredibly silly, I have caught myself a few times pulling-to-refresh my own goddamn static website, as if somebody else was going to post a like or reply to it. I don't know how to feel about that.

Alright, that's probably enough of me for one month. See you when I see you.