Video of this episode is up on YouTube:

I'm about to get on a plane and will be gone for a couple weeks, but didn't want to leave you Breaking Changeless so I did the thing where I stand up in front of a microphone and talked at you. Again. Like I do.

Fun fact: this is the first and only time I've taken a phone call live, on-air! I was just too lazy to edit that out gracefully.

Whenever I go to Japan solo, I experience moments of loneliness, so I'd really appreciate it if you sent me some praise or complaints or ideas to podcast@searls.co and I'll feel comforted by the knowledge that you exist. Your engagement sustains me.

Lotta weird and dumb links this go-round:

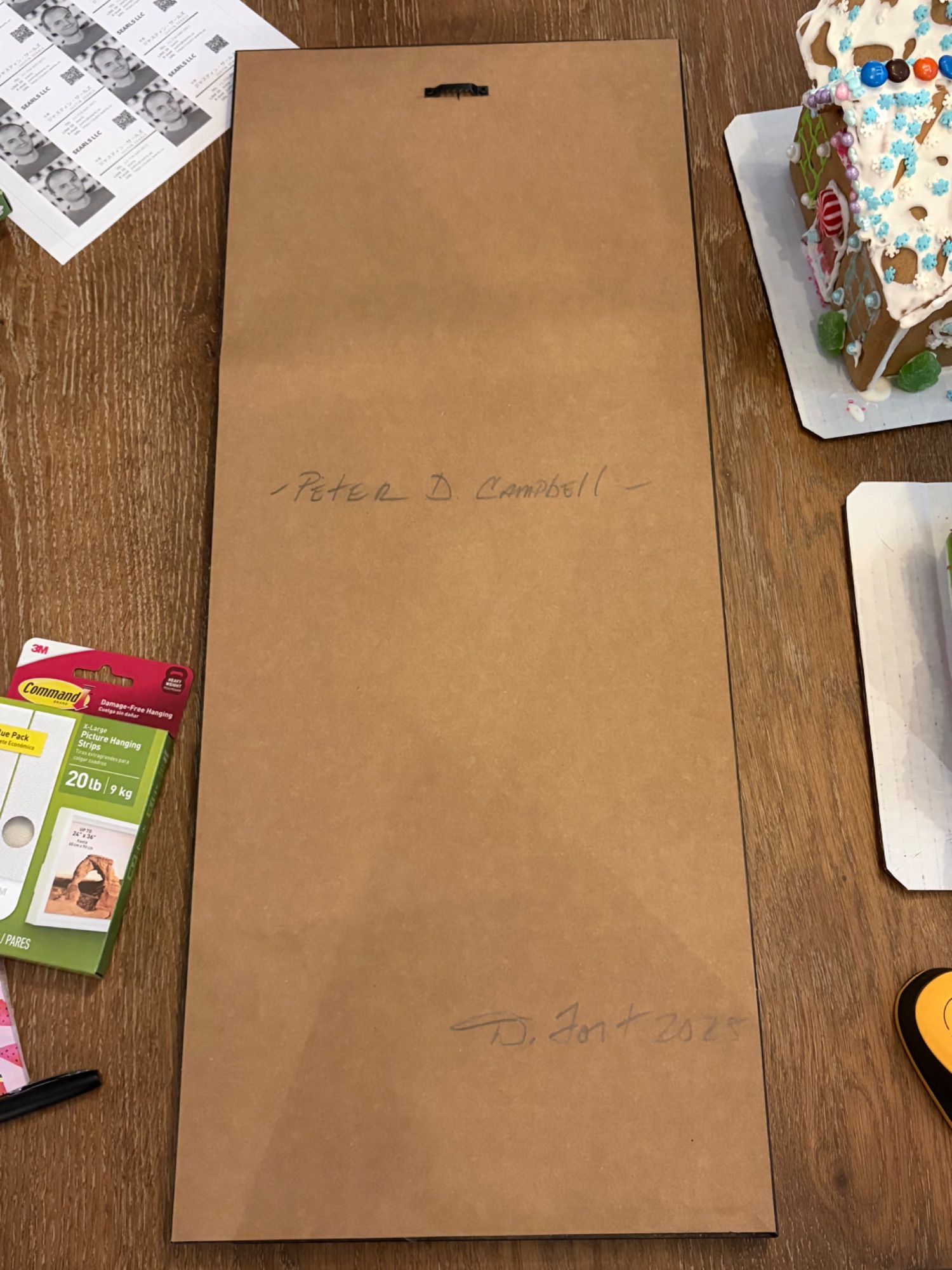

Peter Campbell's giraffe art

Becky and I are wrapping up a rewatch of Mad Men this week, and throughout the first several seasons, she'd point out the artwork hanging near the entrance of Peter Campbell's apartment, a screenshot of which I shall now hotlink from Blogger's CDN like it's 1959:

(Of course, Pete Campbell is so classless that in my head canon, Trudy must have picked this out.)

Anyway, every time the giraffes would show up, Becky would snap her fingers and point at the TV like Leo in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood before commenting on how much she loved the piece. We are not art people, and I can take a hint, so I ordered a recreation made by this guy on Etsy and hid it in a closet for a few months before giving it to Becky to unwrap on Christmas.

Well, I finally got around to hanging them up last night, and they look pretty good! It helps that I had a huge blank wall framed by white trim and surrounded by mid-century modern furniture. I loved the little touch that Peter D. Campbell was written in huge lettering (larger than the artist's) across the center of the middle giraffe.

Classic Pete. What a prick.

TIL that I'm the Napoleon of open source maintenance effectiviology.com/napoleon/

Oof. Adam Wathan and his colleagues on the Tailwind team deserve better. One case where AI is eating a business that was doing right by everyone involved. I bought Tailwind Plus last year to support their work. github.com/tailwindlabs/tailwindcss.com/pull/2388#issuecomment-3717222957

Weekstart

The curse of productivity is that it's self-perpetuating. Respond to e-mails with lightning speed and you just get more replies. Demonstrate your reliability to others long enough, and they'll just bring you more shit to do. Develop productive routines and habits and—before you know it—your natural disposition will shift towards being done with things and away from actually doing things.

Left unconstrained, optimizing for a productive life can diminish the joys of living. Many of us who opt into the lifestyle of "staying on top of shit" do so, ostensibly, to maximize time for creative work, or for leisure, or for family. That's the spirit with which I first discovered Getting Things Done near the beginning of my career. And it really worked! I have no doubt I owe much of my success to adopting a clear productivity process, low-friction tools, and ruthless discipline.

But even for the handful among us who successfully find a productivity regime we can stick with, the technologies that both enabled remote work and unintentionally led to the disintegration of work-life boundaries have resulted in a situation where highly productive people often wind up cursed with the inability to turn it off. I had no problem forgetting about the hundreds of e-mails and things to do in 2009 when I would—get this—leave my computer at the office overnight. But once I started working from home, there was no longer a natural threshold through which to transition from being "productive" to being "unproductive". I doubt I am alone in this.

Depressingly, even after I retired and no longer had any job at all, I found myself continuing to be hyper-vigilant about checking e-mail, tackling todo after todo, and generally prioritizing productivity over whatever shit I claimed to want to do. I've been promising myself a hedonistic life of video games, vodka, and gummy bears since I was 19 years old. And yet, even though I have plenty of money, zero constraints on my time, and a backlog of thousands of games, here I am writing a fucking blog post instead of literally ever doing the one activity I set out to achieve before starting my career.

Moreover, when others look at me and how I go about getting shit done, and—rather than wanting to emulate it—they tend to walk away feeling grateful they're not as tightly-wound as I am. When I consider all the people in my life, it's starting to feel like there are essentially two classes of humans: people who never get shit done and people who never stop getting shit done.

This state of affairs was clearly suboptimal. That's why, last year, Becky and I adopted a bespoke weekly schedule that enables us to get things done without getting carried away. The key insight was, as usual, to implement a strict timebox. We call it "weekstart", and this is how it works.

What is a weekstart?

Weekstart kicks off Monday morning and ends with the dinner bell on Tuesday.

Glad someone else wrote this. IDGAF about macOS Tahoe app icons because they're something I see for a split-second when launching apps, but the new contextual menu icons are far more of a nuisance to trying to use apps. So much visual noise. tonsky.me/blog/tahoe-icons/

100% Oyster Meat

This is a copy of the Searls of Wisdom newsletter delivered to subscribers on January 1, 2026.

As promised last month, this issue is just oyster meat. It's a new year and as good a time as any to hit reset and get this monthly newsletter back on its preordained beginning-of-the-month-ish delivery cadence. That makes this a quick turnaround after our last issue, so there's not much new to report. Good thing I asked you all to lower your expectations!

Let's see, since we last corresponded:

- Mike McQuaid wrote that he's joined the POSSE Party, so I pulled a quote and recruited him to help deal with maintenance and triage. Another early adopter posted an architectural review of my codebase to Reddit

- I spent a few afternoons tweaking a ChatGPT-powered Shortcut for Japanese study and was impressed to find Shortcuts is sneakily more functional than one might assume. Its new Use Model action allows users to tap into cloud-based Private Cloud Compute and ChatGPT for free, which is a total game changer. Native app developers can only access on-device models, which makes Shortcuts a uniquely powerful tool in its own right

- Aaron & I kept the streak alive by executing the 2nd Annual Punsort algorithm. I think his puns got less terrible or I got better at ranking them—either way, things seemed far less contentious than in our first go-round

- I did all four Disney parks in one day and live-wisped the ordeal over 12 hours, 16 rides, and 30,000 steps. If you missed my photos and videos, you'll just have to get in the habit of checking my homepage or Instagram every day, I guess! I got a couple remorseful emails from people looking to find my auto-deleting wisps/stories after they were, in fact, deleted. 💨

- Becky gave me a Steam gift card for Christmas, and this humorous trailer immediately sold me on Ball x Pit. I've since played it and can confirm it to be a Good Game: part Vampire Survivors, part Plants vs. Zombies, part Breakout.

- A few assorted takes:

- If you or a loved one are worried about losing your job to AI, this essay is what I've been pointing people to lately

- Macs have FileVault encryption enabled by default, which has always diminished their utility as home servers—if the power goes out, there goes your remote login access! They finally addressed this in macOS 26 Tahoe: inbound SSH connections following a cold boot will now unlock and finish booting my FileVault-protected Mac Studio

- What populist candidates promise and what they prioritize once elected are rarely in agreement. So it goes in Japan, as an anti-foreigner platform gives way to a policy agenda that will attract more foreigners by further weakening the yen

- If you're running modern Apple hardware, I recently learned there's a setting to make sure Safari actually renders content at a "ProMotion" 120Hz refresh rate

For the second year in a row, us kids paid a visit to dad's second-favorite spot in Walt Disney World on Christmas Day:

Fortunately, gallows humor has always played in the Searls family.

Stay tuned for next month's note, as I'll have just gotten back from the storied land of Shizuoka following the next chapter of our condo purchase journey. We're still on track to close in July, but in mid-January I have the not-technically-mandatory opportunity to pick out the curtains and the drapes at a sort of mini trade show event held by the developer. Well, curtains, yes, but also air conditioners. And tile. And how to finish the balcony. And how many mirrors we want, and where, and whether to tint them in sepia tones. And which LED mood lighting package should line the toilet. Should I pay for them to seal a brand new Japanese wood floor or is that a scammy upsell?

Reply and tell me what to do, please—the decision overload is truly overwhelming.

Anyway, the next week of my life is going to be spent poring over a dozen product catalogs. Bridging the language and cultural divide is extremely slow going. It's a good thing I failed to predict how much work this condo would turn out to be, or I'd never have gone through it. If you catch me having any fun this month, yell at me and tell me to get back to work.

Speaking of bridging language and culture, keep reading for one more stupid thing.

My most-used display has been Vision Pro ever since it launched in February 2024, but it's been used exclusively as a Mac Virtual Display. This is not only because the Mac is a real computer and visionOS is an IMAX-sized iPad, but because its software keyboard is worse than the worst iPhone keyboard to ever be released. And while I'd be happy to pack a travel keyboard, Vision Pro is already too bulky to fit in my bag. As a result, I may as well lug a real computer around with me and just use Vision Pro as a dumb display.

My second most-used display is an iPad mini, which essentially replaces my iPhone when I'm at home. It's set up to be more book-like: an iPhone stripped of any way to communicate with the outside world, with the exception of e-mail. Only problem is that when I do want to type, I'm stuck with what is probably Apple's second-worst software keyboard after visionOS.

My third most-used display is one of a handful of XR/AR glasses—I've been using the XReal Air 2, but am currently trialing the RayNeo Air 3s and Viture Luma Pro. With these, I can use output from any device straight to my eyeholes, so long as it supports DisplayPort over USB-C (e.g., iPhone, iPad, MacBook, Steam Deck). These are great, but once you pair an iPhone or iPad with a desktop-grade display, their lack of a similarly serious keyboard becomes apparent. Besides, when you've got shit on your face, guessing where touch targets are on a screen you can only see indirectly is maddening.

I've wanted the same solution for all three of these modalities: a well-made, pocketable keyboard I could pair with multiple devices. Yesterday, Clicks announced a mobile keyboard that looks like a real contender for solving this problem:

I'm reserving judgment (and praise) until I get my hands on this thing, but the headline features made it an insta-preorder:

- Designed to be held while attached to a phone or as an independent accessory

- Doubles as a MagSafe battery, so it manages to be useful even when you're not using it

- Pairs with up to 3 Bluetooth devices (already bummed it's only 3…)

Little touches abound, too:

- "Batwing" mode, where you can rotate the iPhone to a landscape orientation and—rather than have the display dominated by a software keyboard—actually have the full screen estate for your content while you type

- It appears to have a simple sleep/wake switch, meaning iOS won't banish the software keyboard whenever it's in range

- Quite a few special characters are handled by function keys

Alas, the one thing holding it back is no escape key. Not sure how I'll manage.

$70 if pre-ordered today (shipping in "Spring"), $110 after launch.

Full. Breadth. Developer. simonwillison.net/2026/Jan/2/will-larson/#atom-everything

Shovelware: pdf2web pipeline

Problem: I have hundreds of pages of PDF catalogs in Japanese and no great way to translate them while retaining visual anchors. I like how Safari's built-in translate tool handles images, but it doesn't support PDFs

Solution: point Codex CLI at the directory of PDFs, tell it to rasterize every page of every doc into high-resolution images, then throw together a local webapp to navigate documents and pages. Now I can toggle Safari's built-in translation wherever I want.

Result: I'm no longer worried the curtains won't match the drapes. 💁♂️

This is the golden age of custom software if you've got an ounce of creativity in your bones.

A low stakes, immediately useful task for AI agents would be to stand in for humans in co-op games. I want to play Void Crew, but don't want to recruit friends or party with randos. Wish I could just spin-up a few artificial teammates store.steampowered.com/app/1063420/Void_Crew/

Happy New Year! Need something low-key to watch while you recover? How about a couple hours of Aaron and I shooting the shit as we look back on 2025's best and worst dad jokes in Breaking Change's 2nd annual Punsort! justin.searls.co/casts/feature-release-v48.1-2nd-annual-punsort/

Becky gave me a $100 gift card to Steam for Christmas, so for the first time in a decade I endeavored to hunt for some hidden gems in the Steam Winter Sale. I haven't even booted it up yet, but this trailer immediately convinced me to instabuy Ball x Pit.

I'm sure the game is great, but I wish more trailers were this stupid and irreverent. Gaming is a silly hobby and the best favorite game marketing isn't afraid to embrace that fact.

For a terrifying time, check out what Claude Code produced when asked to "draw a nightmare." reddit.com/r/ClaudeAI/comments/1pxudjr

Video of this episode is up on YouTube:

During the end-of-year podcasting doldrums, I'm pleased to bring you this Feature Release, in which I eschew my tradition of eschewing traditions and present a second annual sorting of the puns. As 2025 (a.k.a. Season 2) of Breaking Change comes to a close, Aaron Patterson once again joins the show to execute our latest iteration of the punsort algorithm.

Following along at home? Here's a spoiler-free link to the original Season 2 rankings.

Ready to be spoiled? Visit /puns for the final pun rankings of 2025.

If you agree, disagree, or are indifferent about where things landed, feel free to get it off your chest at podcast@searls.co.

This perfectly encapsulates the coding agent paradox. Agents make coding boring and formulaic. That some see a tragedy where others see a triumph exposed a disagreement over what coders want out of coding that didn't matter until now reddit.com/r/ClaudeAI/s/VDTxoeiBIh

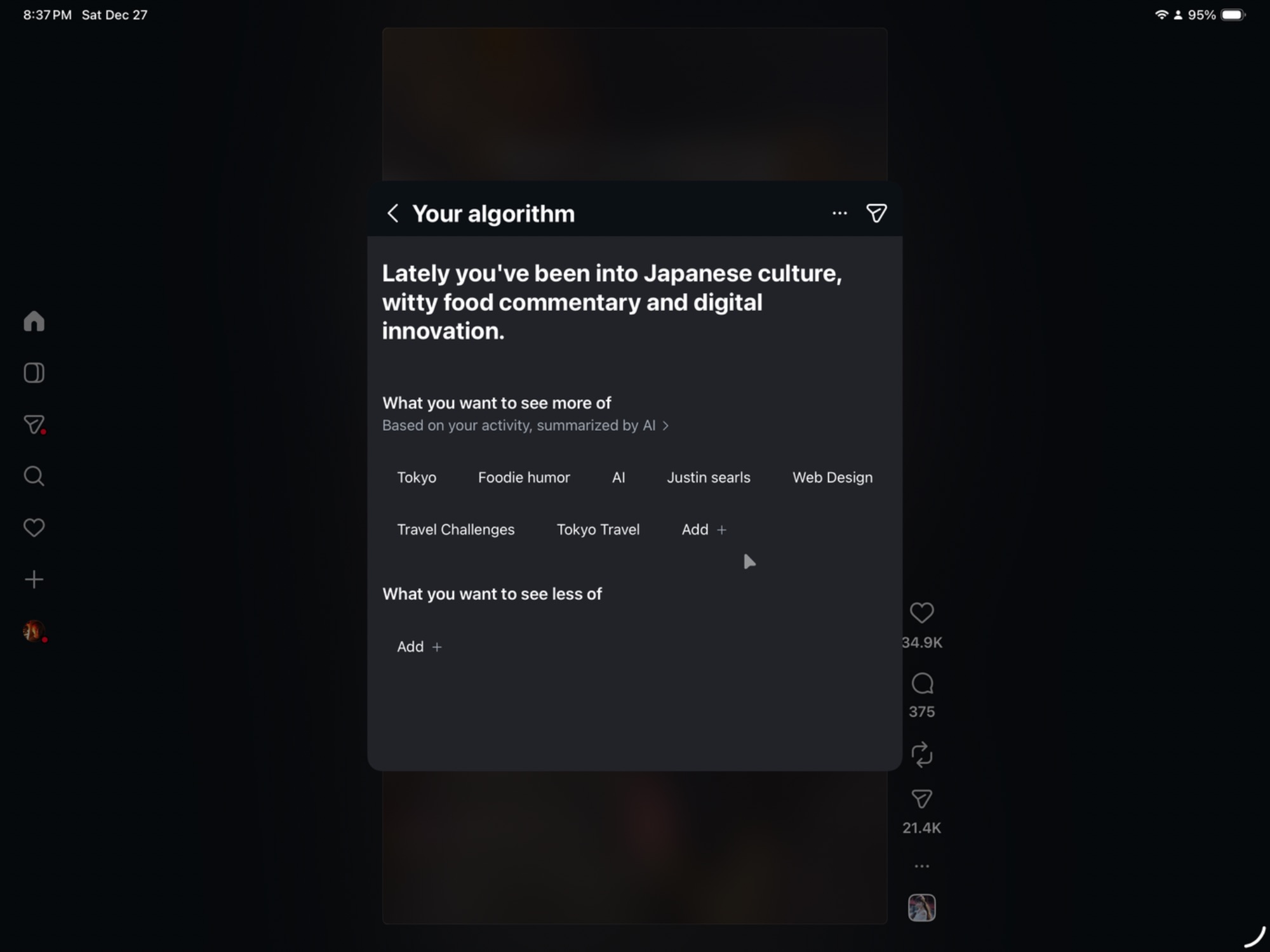

Meta's algorithm has me nailed

If you look closely, you'll spot that the Instagram algorithm has successfully identified my absolute number-one-with-a-bullet favorite topic. How on earth did it figure that out? My phone must be listening to me.