You're looking at my e-mail newsletter, Searls of Wisdom, recreated for you here in website form. For the full experience, subscribe and get it delivered to your inbox each month!

Searls of Wisdom for September 2025

It's me, your friend Justin, coming at you with my takes on September, which are arriving so late in October that I'm already thinking about November. To keep things simple, I'll just try to focus on the present moment for once.

Below is what I apparently put out this month. I'm sure I did other shit too, but none of it had permalinks:

- Added Tot to my (very) short list of apps I use every day, finding it helps me manage the ephemeral text needed to juggle multiple coding agents

- Cut only one major release of the podcast, but did apply two Hotfixes with José Valim and Mike McQuaid

- Iterated on how I work with coding agents. At this point, it is extremely rare for me to write code by hand

- Coaxed said AI agents into building me a tool that automatically adds chapters to a podcast based on the presence of stereo jingles, which I thought was a clever idea (

brew install searlsco/tap/autochapter) - Created a GitHub badge to disclose/celebrate software projects that are predominantly AI-generated shovelware

- Marked one year since "exiting" the Ruby community by giving my last conference talk, then proceeded to entangle myself all over again

- Bought the iPhone Air because I thought I'd love it. Now that I've had it a month, I'm pleased to report it's exactly what I wanted—probably the happiest I've been with a phone since the iPhone 12 Mini

By the way, if you've heard things that make you wonder why anyone would want the iPhone Air (e.g., it looks fragile, it's slower, it only has one camera, it gets worse battery life), this picture was all I needed to stop caring about any of that:

I lift weights, so I know I am literally capable of holding a half-pound phone all day, but I personally just couldn't abide the heft of the iPhone 17 Pro. Carrying it feels like a chore.

To be honest, over the last month I mostly stuck to my knitting and kept my head down trying to get POSSE Party over the line. The experience has been a textbook case of how a piece of software can be 100% "done" and "working" when designed for one's own personal use, but the minute you decide to invite other people to use it, the number of edge cases it needs to cover increases tenfold. Not enjoying it.

Another reason this newsletter is arriving late is that for two days I completely lost myself in OpenAI's video-generation app, Sora. It's very impressive and terrifying! I posted some examples of my "work", much to the confusion of both my hairstylist and Whatever God You Pray To. I also wrote some thoughts on what tools like Sora might mean for the future of visual storytelling, if you're interested.

Interestingly, Sora is designed as a social media app. Its obvious resemblance to Instagram and TikTok is striking. As someone who banished social networking apps from my devices years ago, I (and my wife/accountability partner) was immediately concerned that I was so sucked in by it. But where those platforms addict users into endless passive consumption of content and advertising, Sora's "SlopTok" feed couldn't be less interesting. After you sign up, create your avatar, and follow your friends, it's all about creating your own videos. There is functionally no reason for anyone to visit their feed. Whatever appeal other people's videos might have is dwarfed by the revolutionary creative potential of typing a sentence and seeing your blockbuster movie idea come to life, with you and your friends playing the starring roles.

I guess that explains why I spent so much time thinking about AI and its relationship to creative expression this month. I manually typed that just now, by the way. And an hour ago, I was waffling over whether to manually or generatively(?) fix a bug on my blog. And now I'm typing this sentence right after command-tabbing back into my editor because the realization that everybody is always in the "starring role" on Sora gave me the idea to generate a series of videos where my avatar merely lurks in the background. It is creepy as hell and fantastic.

That distracted impulse to go make a 10-second movie mid-paragraph raises a question: why do I so thoughtlessly reach for AI to generate videos, but agonize over whether to use it to write code? And what does it say that I categorically refuse to let LLMs write these essays?

Greetings, because that is today's topic.

The Generative Creativity Spectrum

Add creativity to the long list of things I've had to fundamentally rethink since the introduction of generative AI. Up until that singular moment when Stable Diffusion and GitHub Copilot and ChatGPT transformed how people create images, code, and prose, I held a rather unsophisticated view of what it meant to be creative. If you'd asked me in 2021 to distill the nature of creativity, I would have given you a boolean matrix of medium vs. intent. I'd probably hammer out three bullets like these:

- Writing: drafting a policy document at work is not creative, but writing an essay like this one is creative

- Coding: tweaking a hundred integration tests in order to upgrade a dependency is not creative, but making an absurdist emoji-based programming language is creative

- Visuals: composing a chart or illustration to make a point in a presentation is not creative, but painting a fresco of a chihuahua in heat is creative

And I probably would have felt good about those heuristics, as they represented the extent of my thinking on the matter. (Or on chihuahuas, for that matter.)

But as AI tools have become so distressingly competent in these three short years, many of us have had to renegotiate our relationship to creative and artistic endeavors. Why, for example, am I so happy to throw caution to the wind and spend two days generating stupid videos in Sora without the briefest hesitation or twinge of guilt? Why am I so torn about coding agents, simultaneously feeling both excitement and sorrow? Why am I so protective of my writing, going out of my way to avoid LLM-based writing tools for any purpose beyond checking my spelling and grammar?

I spent some time noodling on this, and here's where I landed: whether I embrace or reject an AI's assistance depends on whether the creative act's value to me is internal or external.

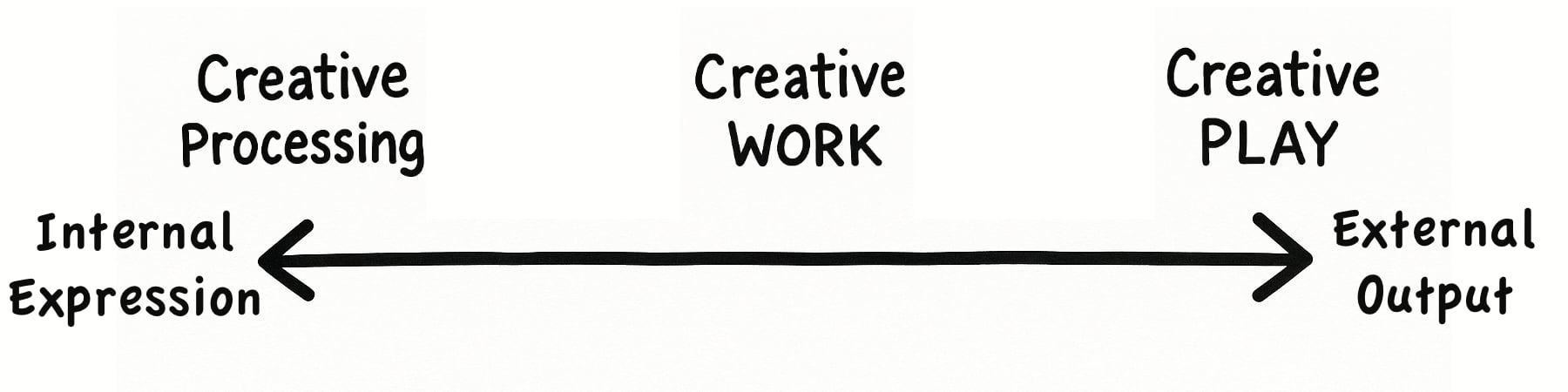

Below is my best attempt to diagram generative creativity as a spectrum:

Breaking this illustration down:

- Creative Processing: The left side represents activities where creativity's benefit is internal (e.g., processing intimate emotions, unlocking key insights). To use AI for activities on the left would rob them of all their value

- Creative Play: The right side is for creative activities whose value depends on what it does for other people (e.g., communicating a concept, getting paid to update a corporate logo). Using AI for these tasks is a no-brainer, because you'll get more shit out the door faster than ever

- Creative Work: The murky middle is reserved for activities caught in a sort of limbo between their internal and external value (i.e. practicing a skill that both pays the bills and offers a sense of purpose). What the hell do we do with these? Embracing AI effectively trades increased capability and productivity for decreased understanding and fulfillment

Below, I'll lean on a few examples from my own life to navigate the spectrum in more detail. Depending on how you personally express creativity, an activity that's at one end of my spectrum may be at the opposite end of yours—fear not, that's a good thing! Different creative acts mean different things to different people in different contexts.

Let's start by exploring the use of AI to create visuals like images and video.

Generating Visuals with AI

Note that we're discussing "visuals" broadly and not "visual artwork" specifically, here. Not all visuals are art, and not all art is visual. Plenty of visuals effectively exist as glanceable, information-dense communication, but hardly register as art (e.g., reaction memes, social image thumbnails, most of your TikTok/Instagram feed).

I took drawing classes as a kid. A well-known illustrator actually came to my school and did a lesson for us. I bought his book and spent an entire summer practicing. And for all my hard work, I was rewarded with absolutely fuck all. All those hours of practice and I rarely made it past step 1 of each exercise (forget the rest of the owl, I couldn't draw two circles right). Years later, I saw the author again at a bookstore event and explained my predicament, asking his advice. He kindly suggested that maybe drawing wasn't for me.

Ever since, I've felt creatively hobbled by my incompetence at visual communication. It was only through sheer force of will that I was able to produce so many Keynote presentations containing 400–500 slide builds—maybe this additional context will help you understand why those talks always took me multiple months to prepare.

Nevertheless, I'm a highly visual person. Ideas often come to me as images and then I work backwards into language. I think of a dozen things each day that would be better communicated with a picture or video than a verbal explanation or analogy. For most of my life, I lacked the time and skill to express myself visually as often as I would like.

Last week, a comic on The Oatmeal went viral for the artist's pointed case against generative AI. I found myself sympathetic to the human but not his argument, because it portrayed the same one-dimensional view of creativity I described earlier:

"Even if you don't work in the arts, you have to admit you feel it too—that disappointment when you find out something is AI-generated" – Matthew Inman

And here's the thing: I don't have to admit I feel this way. Pictures and paintings don't do anything for me emotionally or expressively. Never have. Perhaps my childhood development was stunted or maybe I'm put together wrong, but visual artwork has never frothed my loins. If paintings are hiding some secret loin-frothing gear, nobody showed me how to shift into it. In fact, I wish I could look at an AI-generated image and feel disappointment. At least then I'd feel something.

Instead, my relationship with visual creativity is entirely as a low-stakes communication medium. It hides no deeper meaning. It expresses no emotion. Because visual art serves no internal purpose for me, my only use for it is as a communication medium. That frees me to create and experience images and videos as pure and simple fun. It's truly joyful for me, even if it's all slop. To be honest, since Sora came out, I haven't had so much silly fun playing with my computer since I was maybe twelve years old.

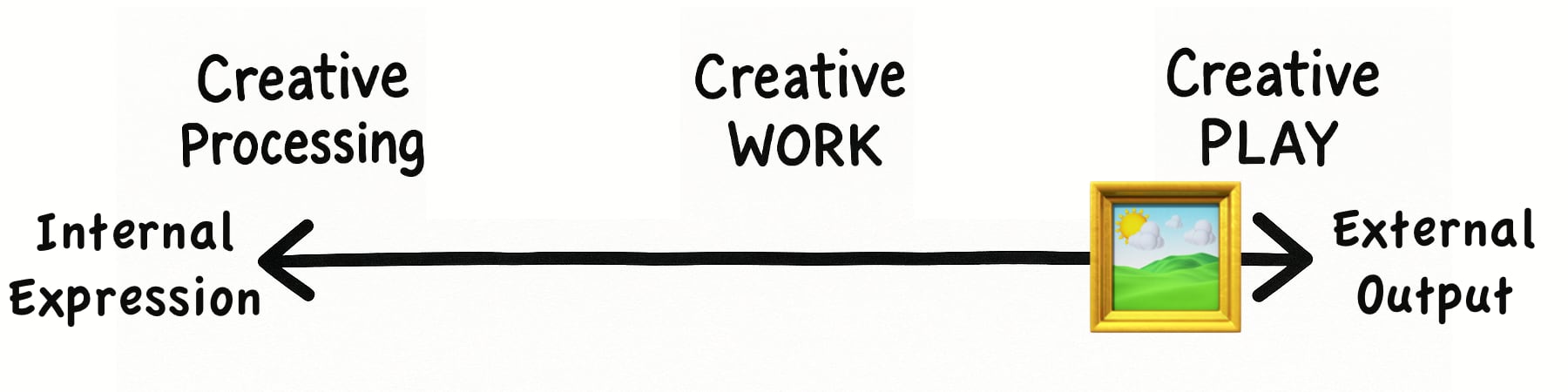

That's why my use of tools like Sora to communicate concepts sits at the far right side of the spectrum as "Creative Play":

If you're a visual artist, you probably feel differently. And if that's the case, then your creations serve a different purpose to you than mine do to me. I have deeper creative needs too, I just get them met elsewhere.

Generating Code with AI

Something that means more to me than pictures is code. Learning to program at a formative age taught me how to think clearly, how to combat overwhelm, and how to contribute something of value to others.

In November 2022, I had toodled around with "AI" coding tools a bit here and there, but—given that it would be a month until ChatGPT was released—the scope of their potential hadn't really clicked with me yet. Having heard so much buzz from inside the Copilot team, however, Todd and I decided to do one last(?) sales trip together to visit GitHub, one of our all-time favorite clients. We attended their Universe event in San Francisco, and GitHub's (well, Microsoft's) message was clear: they were betting the company on this AI shit.

I was skeptical, but signed up for GitHub Copilot anyway. I enabled the feature and forced myself to stick with it. A few months later, I did a limited screencast series called Searls After Dark, in which I live-coded a basic LLM chat app. Because I had GitHub Copilot turned on, if you go back and watch those videos, you'll learn two things: Copilot's autocomplete suggestions were almost universally terrible, and nearly every bug and derailment I experienced was caused by Copilot distracting my train of thought. Over the course of ten episodes, I got a dozen e-mails from viewers pleading with me to turn off GitHub Copilot, because it was making them angry.

Those viewers were right that v1.0 of "spicy autocomplete" was too distracting to be useful. But its (very) occasional flashes of brilliance, paired with the knowledge it could only get better from here, convinced me to stay plugged into each new iteration of AI code generation tooling. That way, I'd be prepared to pounce as soon as the tools reached the point of being worth my time.

It's been a bit stop-and-go, but I've been working on this app called POSSE Party all year. Because I keep picking it up and putting it down, these short bursts of development have created a slideshow illustrating how quickly these tools are moving:

- In January, I wrote the foundation of the application, the static marketing pages, and the first several platform integrations entirely by hand. I had GitHub Copilot autocomplete enabled, but rarely accepted anything it suggested

- In June, I built the next 5 integrations and a basic user interface in a hybrid model, using a combination of Cursor's superior autocomplete and its nascent agent-ish YOLO mode with the Claude Sonnet 3.7 model. This was more productive than coding without AI assistance, but was hobbled by Cursor's asymmetric pair-programming style, which required me to rapidly review each tiny change and rush to prompt it with the next bite-sized task

- It's now October, and I've moved on to GPT-5 and a fully-autonomous Codex CLI agent. Today, it's rare for me to code anything by hand, because agents are just good enough to be good enough. Tuesday of this week was notable, because I spent the entire day eschewing agents in favor of brain coding a complete rewrite of my Instagram adapter—it almost felt nostalgic

To experience such a dramatic transformation firsthand in only nine months' time is nothing short of remarkable. Programming as I've known it for most of my life will never be the same. Yes, I'm still allowed to write code by hand, and yes, these agents aren't half as smart as me, but they make up for it with a productive relentlessness I could never compete with. And the tools are only going to get better.

All of the above can be true, but it doesn't mean I have to be happy about it.

If you follow my work closely, you've probably seen or heard or felt me complaining about how much I hate the experience of working with AI coding agents. The routine disappointment when agents don't do what I want. The frustration of repeating myself when they refuse to incorporate my feedback. The frazzled stress following a long day bouncing between a half-dozen chat windows.

I'm no stranger to the creative process being excruciating, but coding with agents feels less like I'm thinking deeply to solve problems as a programmer and more like I'm wasting all day in Slack and Zoom as a manager.

But what the hell am I supposed to do? I'm haunted by the knowledge that I'm going 2-3x faster than I otherwise could, and maintaining a similar level of quality. I'm mournful of the fact that going back to a peaceful, engaging, and rewarding workflow of programming by hand would drastically reduce my productivity.

Under my previous one-dimensional concept of creativity, building a new app is undeniably and straightforwardly a creative endeavor. Working with coding agents has given me cause to reevaluate my programming efforts along this new generative creativity spectrum, however. I don't have a job, so I could just say "fuck it" and code strictly for the intrinsic benefit of learning and overcoming challenges. At the same time, I don't sit at a computer all day for my health, so I could just vibe code the tools I need and only concern myself with their extrinsic utility. And in truth I spend a little bit of time programming at both of those extremes.

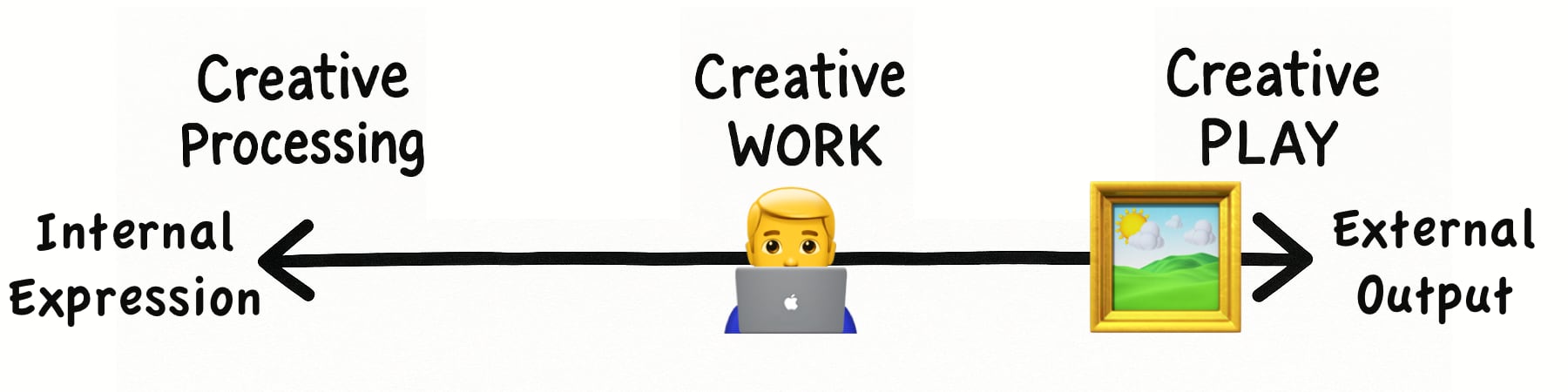

But upon reevaluating my decades-long relationship with my craft through this new lens, it's become clear that programming sits in the middle of the spectrum as "Creative Work." I wouldn't bother writing a program if it weren't for whatever useful thing I needed it to do. At the same time, I rely on programming to fulfill a sense of vocation and to keep my mind sharp.

This newfound awareness that I suddenly have to compromise between internal enrichment and external productivity explains why I feel so uneasy in this new era. I honestly hope this isn't the final shape of the AI codegen landscape, but for now that's where things seem to be landing and that's where I sit.

Generating Writing with AI

One place where I don't have any reason to compromise, however, is my writing. I categorically do not use AI to generate anything I include in this newsletter or post to my website.

The reason I don't generate prose isn't that LLMs are bad at writing like I do (although they are). If that were the only thing holding me back, presumably I'd eventually reach the point—like I did with code—of handing the wheel to ChatGPT and shifting my task to steering an LLM along my outline and toward my intended conclusion. No thanks.

The actual reason I would never generate these essays is because the act of writing itself is what brings me value. The benefit exists entirely between my ears in the form of deliberate introspection and self-discovery.

Not only does writing make me no money, but essays like these offer me no extrinsic utility after I've written them. My purpose for writing (besides as a way to keep dear friends like you aware of my continued existence) is buried deep in the soil of my mind. The toil of wrestling with conflicting ideas and resolving inner conflict is what unearths this value, organizes it, polishes it. Publishing a piece simply places the resulting artifact in a display case above ground and in clear view.

Writing for this purpose is slow and painful. A third reason it took me so long to write this month's essay is that I extremely did not feel like doing it. But like brushing my teeth and eating my vegetables, I know it's good for me. I'm a financially secure, functionally retired 40-year-old and yet I assign myself this homework each month to ensure I'm always grappling with deeper questions than I otherwise would in the course of my daily routine.

If you've been reading this newsletter for a while, one thing you don't see is the fact that nearly every essay ends up being about a topic or making a point that is wholly different from what I'd originally intended. Here's how it goes. I'll have an idea and add it to a list. Some morning when I'm otherwise between projects, I'll grab my notepad and write a few pages over an hour or two. Later, I'll grab an iPad and type out six hundred words before realizing I lost track of my point halfway through. I'll go for a run, then tinker all afternoon to pound those words into a reasonable rhetorical structure. By dinner time, I'm exhausted and staring at two thousand words that somehow fail to convey the simple idea I had started with. "Well, fuck," I'll inevitably think to myself every goddam time, "I hate this. I'm extremely bad at this."

Writing is not fun and I love it.

But then, whether that night or in the shower the next morning and amid the simmering anguish in the back of my mind, somewhere beneath my crisis of confidence, I will hear something happening inside of me. It's as if a brass puzzle box hidden away in my psyche began to make a clicking sound. Its interlocking gears start turning. As I listen closer, I hear the satisfying plunk of pinions pushing into tumblers, as if unlocking a conclusion I never consciously set out to make.

What's in the box? It depends. It could be a sense of calm following the loss of a loved one. Or a deepened acceptance of some small part of myself. Or a renewed resolve that I've been right all along, and it is indeed the children who are wrong.

What's counterintuitive about my relationship with writing is that the text on the page isn't the key to opening the treasure chest. In fact, the sum of what I write isn't a solution to anything. This essay, or that blog post, or the last over-torqued e-mail I wasted a whole afternoon on is merely an echo of a solution. What actually unlocked the puzzle box was the struggle itself. Think of your favorite song. The magic is not hiding somewhere in the sheet music—its impact is only felt through the act of playing it. Over the years, this torturous misery of writing has occasionally caused my brain to fire the right neurons in the right order and at the right tempo to eventually lead my conscious self to watershed moments that have profoundly impacted my life.

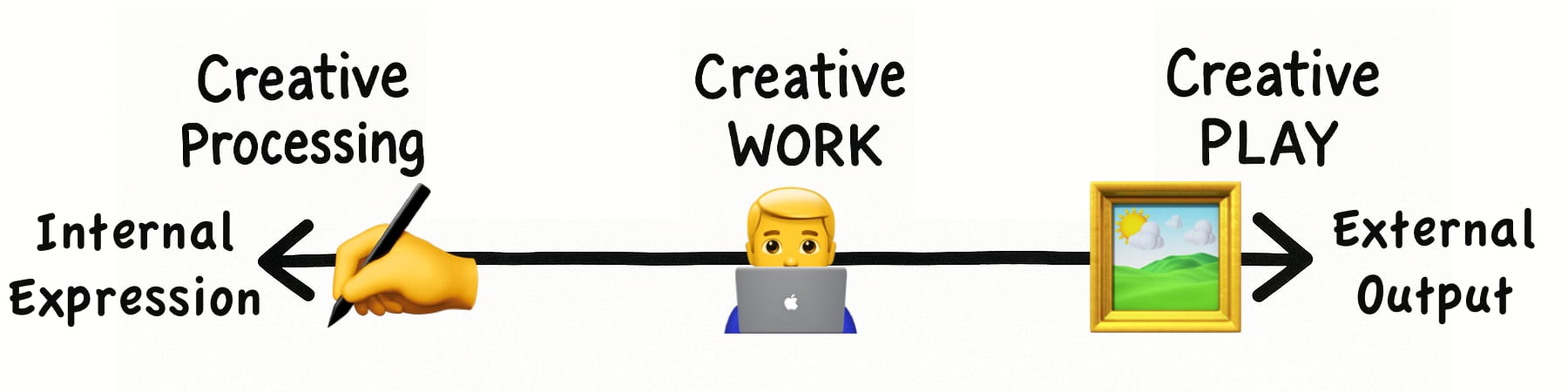

In case it isn't already obvious, and because I'm a completionist who can't leave an illustrative figure unfinished, for me, writing sits at the left end of the generative creativity spectrum as a form of "Creative Processing":

For you, maybe your creativity processing occurs while you play the accordion. Or practice calligraphy. Or design choreography. Or maybe you don't process creatively at all. There are no wrong answers.

The Career of Creativity

I am aware I have ignored the elephant in the room.

What about people who make their living off creative work?

There are several ways to tackle this question. The one-dimensional paradigm of creativity can only provide one of two unsatisfying answers:

- They are fucked

- They are not (or should not be) fucked

Virtually everything I've seen written about the impact generative AI will have on creative careers starts with one of these conclusions and then dresses it up with rationalization, justification, and exhortation. Limited to this framing, I guess my best answer is, "they are fucked and that is very sad."

However, if the answer were really that simple, then people in creative jobs would be succeeding or failing together as a single monolithic demographic. But that's not what seems to be happening. Instead, I know some creatives who are absolutely thriving right now. I know some who are out of work and in dire straits. Others are getting by, but as employer expectations shift and roles change, they're reckoning with what feels like a personal loss.

- External Value: If you show up to work to crank shit out, aim to please by creating whatever's asked of you, and use the word "content" to describe the things you make, you're probably as happy as a pig in shit right now. The absolute explosion of tools allowing you to branch into new media and to supercharge your productive output are likely already setting you apart from your colleagues. Your value to The Market is likely to be seen now more than ever, and that's in spite of the deluge of slop that's consuming the web and the publishing industry

- Internal Value: If you managed to make a living by painstakingly producing labors of love that primarily served to meet your own needs, then I hate to say it, but you were lucky to have ever gotten paid for it in the first place. As demand for creative professionals decreases and expectations for individual output increases, the return on investment for this kind of work—unless you're some kind of genius or celebrity—will probably never again be enough to earn a living wage

- Everybody Else: If you're somewhere in the middle on this—getting paid for output that meets an external purpose but from which you also derive some internal value—you're probably as torn as I am about what the fuck to do about programming. Some people are responding to the potential diminishment of that intrinsic benefit as a threat: they're fighting back, refusing to adopt new tools, and getting added to a list of who to let go during the next round of layoffs. Others, meanwhile, see this as an opportunity—that by increasing their productive capacity, generative AI can dramatically increase the scope of their creative ambitions. Which side you'll land on is ultimately your choice

Even though I write for me and not for you, I'm grateful that you read this. I'd also be glad to hear how this essay made you feel and what you think about all this. Shoot me an e-mail if you have a minute. And if you'd like me to discuss some aspect of this on the podcast, write in to podcast@searls.co. 👨🎨